Agrarian Commons closely resemble community land trusts, but they are unique in that they work collectively to provide long-term affordable and equitable access of small and mid-sized farms.

by Ian McSweeney and Darby Weaver

Originally published September 20, 2019 on Shelterforce

It’s estimated that we’ll see upwards of 400 million acres of farmland in the United States change hands over the next two decades as a generation of farmers and ranchers retire.

The elders in agriculture are doing their best to hold onto the tattered threads of skills and trades that have been passed down from generations of food producers and land stewards, knowledge that is slowly being lost due to obstacles that prevent fresh hands and eager minds from securing farmland. With the average age of farmers in the United States being 58, it has become imperative that a new generation of farmers step up to breathe new life into farms and landscapes that run the risk of being developed, gentrified, or sacrificed to the seemingly unstoppable blight of poison-ridden, heavily mechanized, single-crop-producing, sterilized land. To choose to farm today is a heroic task with few rewards, and yet somehow, within the pressure cooker of all of these forces, a new generation of land stewards is emerging.

These first-generation agrarians struggle with land access, affordability, and tenure. They are coming into farming often with limited resources, student loan debt, and are attempting to start a business on land that has been priced far outside of the economic viability of their proposed business’s profitability. The value of land—which ranges greatly across country as the same type farmland can sell for $300 to $400 per acre in one area, to $200,000-plus per acre in another—is based on an appraiser’s determination of highest and best use. The appraiser uses certain qualifiers to decide how suitable the land is for extraction or development and does not consider the natural value of a space or its ecological suitability for agriculture, unless top soil, aggregate, or timber are available to remove and sell for profit.

Farming elders often need to sell their farms based on the highest market value in order to cover mortgage debts and health care costs. Additionally, the bottomed-out price of agricultural products due to government subsidies, commodity farming, and a culture that does not value, choose, or pay for real food, generally finds farmers with little to no savings for retirement. Selling their farm to the highest bidder becomes the only means for financial stability in old age, and this means that the land is often acquired by Big Ag, development corporations, wealthy estate buyers, or foreign investment capital interests—entities that seek the land for extraction, development, or speculation.

How the Commons Works

At Agrarian Trust, we believe it’s time to chart a new way forward. We see the need to hold agricultural land in a community trust to ensure that elder farmers have the opportunity to pass on their craft while also preserving the ecological communities within a diversified, sustainable operation. These farms and agrarian properties not only serve as tools for reviving rural communities and bolstering small-town economies, but they also tie together the severely fragmented natural world. In the face of a changing climate, we have prioritized the importance of bringing people back in tune with the landscape knowing that this is the only holistic means for bringing empowerment, equity, and prosperity all while simultaneously allowing the Earth to tap into the replenishing homeostasis of regeneration. In the words of Malcolm X, “Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice, and equality.”

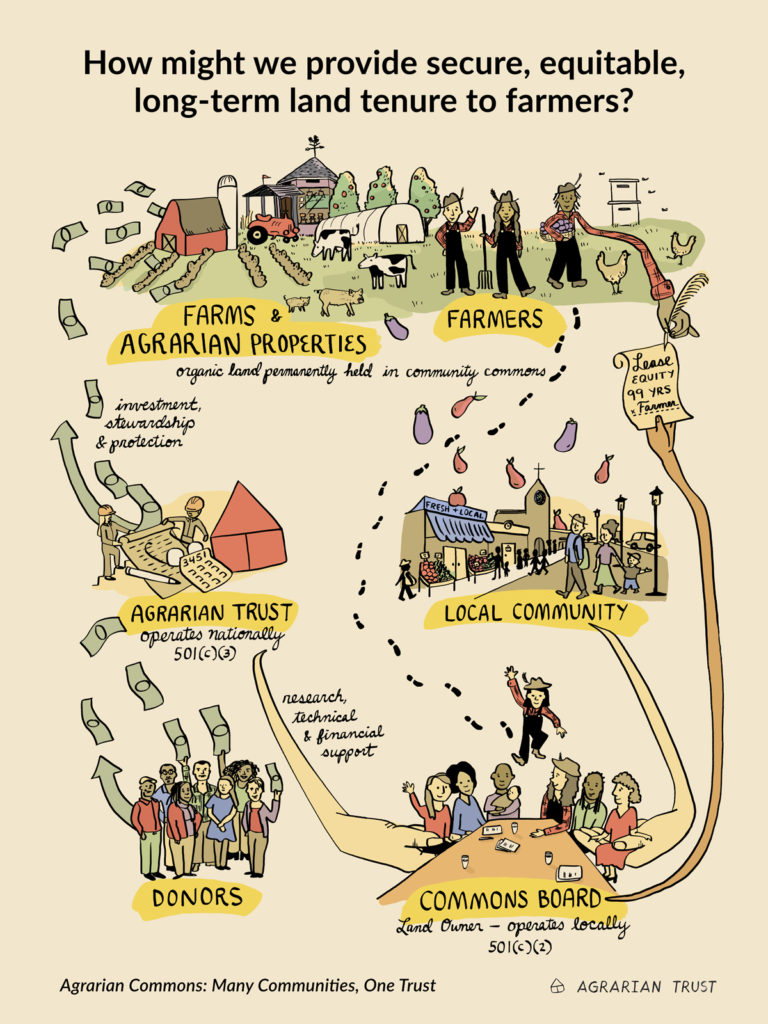

From its origins in 2013, the goals of Agrarian Trust have been based on a desire to provide land access to new agrarian communities and allow each individual group to establish its own system of management and leadership, influenced by identity of place. Agrarian Trust has steadily developed the Agrarian Commons model since 2016. The commons are multiple 501(c)(2) community-based landholding entities across the country that provide long-term equity leases of farmland and property to farmers and other agrarian enterprises. While the commons most closely resemble the community land trust structure, the focus on farms and the collaboration with multiple local farm-based CLTs that are aligned collectively is what makes the Agrarian Commons model unique. Here’s how it works:

- The local Agrarian Commons buys properties from farmers and farmland owners in their region through the support and fundraising efforts of the national Agrarian Trust.

- The local Agrarian Commons leases those farms to farmers using a long-term affordable and equity-building lease (99-years when state law allows).

- Each local Agrarian Commons is governed by farmers who hold leases, community stakeholders, and the Agrarian Trust.

Growth in the Agrarian Commons model occurs in a healthy natural state and everyone involved has a voice and a direct and personal relationship with the landscape and organization. Agrarian Commons develop five to six 501(c)(2) legal landholding entities at a time, with each starting with at least two farms and growing to not more than 10 to 12 farms.

Agrarian Trust is now engaged with 10 farms/ranches that will create five Agrarian Commons in five states across the country. Interest, opportunity, and early stage discussions also exist between Agrarian Trust and another 15-plus farms that would create another five Agrarian Commons in five states.