From Modern Farmer

Francesco Galante works for a network of organic farmers called Libera Terra. Get him talking, and he’ll go on and on about their delicious pastas and oils and the depth and complexity of their wines. It almost slips his mind: Everything was produced on confiscated Mafia property.

Way back in 2001, the Cooperativa Placido Rizzotto set up shop in Sicily, right in the heart of Cosa Nostra country (the village of Corleone, birthplace of the fictional Vito Corleone, was just a few short miles away). The cooperative began selling food under the label Libera Terra, or “free land.” It was the first beneficiary of an Italian law that provided former Mafia land to farmers.

Naturally, farmers were leery to hop on board. Free land was enticing, but what payback would they face? “When we first started, nobody from the towns nearby wanted to come and thresh our wheat,” the cooperative’s vice chairwoman told the Global Post. “Cultivating seized land was something unprecedented, and people didn’t want to be seen as working for us.”

Italy brought in military police to guard the threshing; food producers slowly gained courage. The next few years saw a handful of violent incidents — one Libera activist talks about burned vineyards and stolen tractors — but things were mostly tranquil.

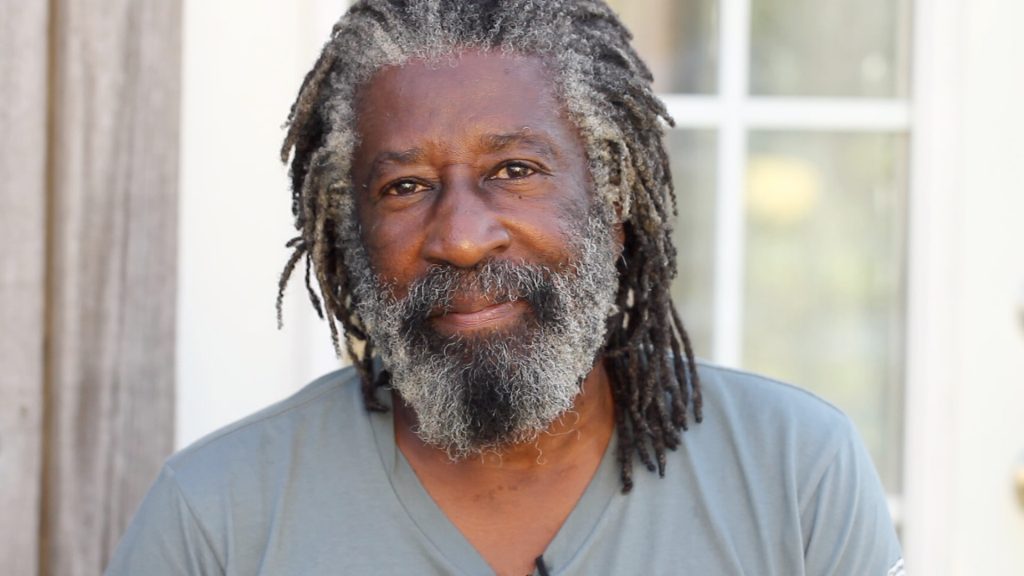

Each Libera Terra wine bears the name of a slain mob victim; products are marked both organic and “Mafia-free.” Galante, product manager for Libera Terra’s wines, says it took three or four years for co-op members to really become comfortable with the concept. “That’s when people started to look around and realize we didn’t have to worry about the consequences of taking this land,” he says.

One of the seized properties belonged to Giovanni “The Pig” Brusca, a man jailed for committing 100 to 200 murders (he claims that he doesn’t remember the exact count). You’d think Brusca’s cohorts wouldn’t look too kindly on Libera Terra renting his farmhouse to agritourists. Or Nitto Santapaola, aka “the Hunter,” called “one of the most bloodthirsty godfathers.” His land now produces a jasmine-flavored orange juice.

What Retaliation?

Much like their counterparts in the U.S., Italian mobsters have lost ground in the last 15 years. Intensified prosecutions have resulted in a severe diminishing of the Mafia’s menace. Not to mention the civilian uprising: Libera Terra grew up alongside the Addiopizzo movement, a group of Sicilian businesses which refuse to pay protection money.

But even if the Mafia still had its power, Galante thinks Libera Terra’s members would be safe. After all, the farmers don’t own the land they’re working — the government does. “Why would they try to punish us?” he asks. “We are a weak target, too little for them to bother with.”

Initially, Galante says customer interest was mostly about social responsibility — the products weren’t actually that great. Like buying something with a Fair Trade or Rainforest Alliance label, Italians were making a political statement with a Libera Terra purchase.

But over the years, the farmers and artisans involved with Libera Terra — there are now more than 200 — started focusing on quality. The brand shifted tones, marketing its products’ flavor and sustainable origins.

“These days people are interested in knowing about our organic farming methods, and that our producers are treated fairly,” says Galante. “That’s why they buy Libera Terra.”