Ensuring Donated Land Gets Managed Equitably

For Callie, successfully conserving agricultural land with issues of racial equity and environmental sustainability in mind took a lot of time and plenty of careful planning. After inheriting the land in 2015, Callie enrolled in classes at the local college and attended conferences on biological farming in search of farmers who shared her vision. Callie found a number of farmers who were interested in working the land, but only one couple was able to make a long-term commitment. Finally, after years of looking for a good fit, Callie and her husband found the Agrarian Commons model.

Building the Foundations for Food Sovereignty at Lick Run

Community engagement and youth education play key roles in Terry’s vision for Lick Run Farm—even when it comes to creating a viable farm infrastructure. Building a greenhouse, Terry pointed out, can be an opportunity for teens to acquire important career skills.

“Something I learned firsthand when I first started farming was that farming is so much more than raising plants,” said Terry. “You at least have to be competent with plumbing, carpentry, maybe even a bit of electrical work.”

Ostrom’s Eight Design Principles for a Successfully Managed Commons

Torbel came to international attention in 1990, when Ostrom published her groundbreaking study of commons, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. In the book, Ostrom argued against the dominant understanding of the commons, as exemplified by Garret Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons, which held that the commons would inevitably—and tragically—be depleted by rational, self-interested actors. The existence of communities like Torbel was evidence enough for Ostrom that Hardin’s model was too abstract.

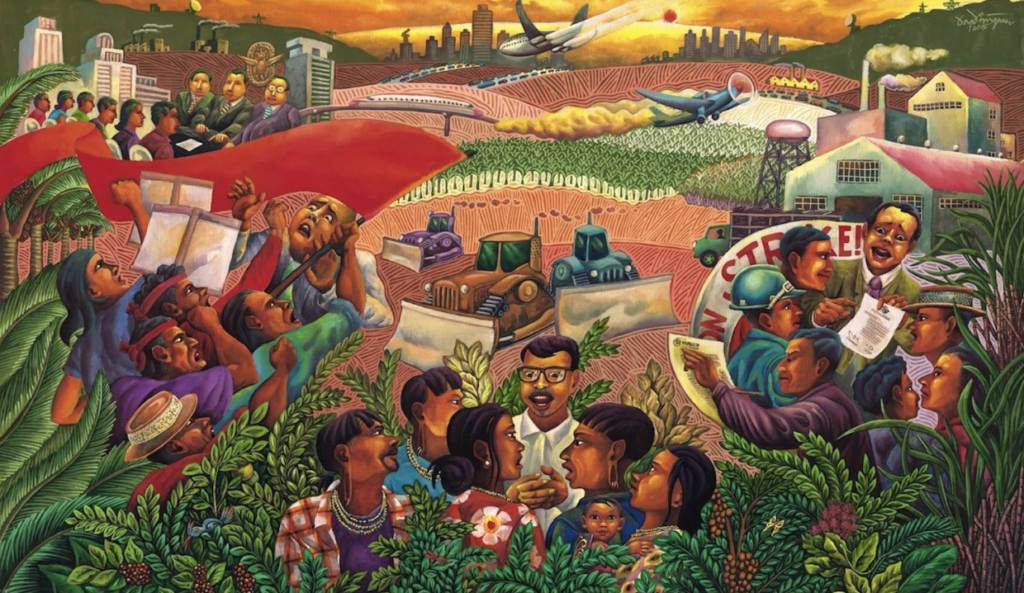

La Via Campesina

La Via Campesina coined the term food sovereignty in 1996, against the background of an increasingly globalized food system, which heavily favored large agribusinesses over small-scale farmers. The World Trade Organization (WTO) pressured countries to dismantle their local agricultural system, to lower prices, and become competitive on the global market. In order to drive labor costs down, farming became increasingly centralized, driving peasants and Indigenous people off their land at unprecedented rates. Aggressive copyright law and genetic engineering by large agribusinesses robbed peasants of their seeds, rendering them reliant on a volatile global market of pesticides and genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Cheap produce flooded local economies, destroying the livelihoods of farmers who were unable or unwilling to compete.

What can we learn from Deshee Farm? A Visual History

While farms like Deshee failed to take hold in the United States and had significant limitations, its story serves as a reminder that the privatized corporate farming that dominates U.S. agriculture was anything but inevitable. Grassroots organizing by tenant farmers played a key role in securing innovative, state-funded programming whose scale and vision matched the needs of the moment. Had there been more resources to fund similar efforts and more time and autonomy for the members of RA farms to develop the necessary institutions and cultural practices to effectively govern their shared resources, we might have been living in a different, more cooperatively focused world.

Commodity or Commons: Finance Capital and the Commodification of Land

The first major entity to begin investing in farmland as an asset was Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA)—one of the largest pension firms in the United States, with $1,375 billion in assets. In 2007, the TIAA began purchasing enormous tracts of land. By 2017, the TIAA owned more than 1.9 million acres of farmland worldwide— an area significantly larger than the state of Maryland—including over 490,000 acres in Brazil alone. TIAA’s purchases in Brazil led to the consolidation of power in the hands of a small number of agribusinesses specializing in soy monoculture, driving farmers off their traditional land in record numbers, and leading to widespread deforestation, wildfires, and loss of biodiversity.

Studies of the Agrarian Commons in the Higher Education Community

The Agrarian Commons model, now in its implementation phase, is being studied by researchers, professors, and students throughout higher education and law school institutions.

Mark Lancaster Joins Agrarian Trust as Development Director

There is little doubt that over the next 5-10 years upwards of 400 million acres of land in the U.S. will change hands as farmers and ranchers retire. What will happen with that land is of great concern to me and to Agrarian Trust.

Healing the Land Through Community Collaboration in the Southwest Virginia Agrarian Commons

As the campaign to raise $426,250 to purchase Lick Run Farm gains momentum, the Harvest Collective, a Virginia-based collaborative farming group, is already hard at work preparing Lick Run for its new place in the Southwest Virginia Agrarian Commons. Along with Cam Terry, the head farmer at Garden Variety Harvests, the collective has been mowing grass, laying tarps, and completing small construction projects around the land.

Fighting for Domestic and Global Food Sovereignty

The high cost of land, racial inequity and land grabbing that underpins agriculture in the United States is part of a global trend of expropriative land practice, founded upon centuries of corporate greed and colonial violence. Agrarian Trust is an active member of a global movement that seeks to heal from these destructive forces, while charting a new path forward—beginning with Indigenous knowledge, local control of the land and agroecological growing practices. Since its founding in 2010, the United States Food Sovereignty Alliance (USFSA) has worked “to end poverty, rebuild local food economies, and assert democratic control over the food system” as a partner organization of the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty.