Richmond, Virginia’s capital, is unique with its rolling hills, large boulevards, and grand homes, many constructed on ample lots at the turn of the century. It’s a city where each home seems to have a story and a place in history. During the 1930s, the federal government redlined many of the beautiful homes in the central downtown area, in the neighborhoods of North Side, Gilpin, Jackson Ward, Church Hill, and Randolph. Redlining was a red mark against these robust neighborhoods, meaning that they could not connect to federal funding for home loans. Race was the defining factor in redlining and prevented these communities from gaining full access to the federal support that was needed and that they paid into through the federal tax system.

Some would think that this method of housing appraisal in the past would have no impact on the present day, but that is a fallacy. These beautiful neighborhoods that were redlined last century are now experiencing some of the hottest temperatures in Richmond. They have the least amount of trees and the highest amount of heat trapping pavement in the city. During the hot summers of the south, these neighborhoods have some of the highest rates of heat-related ambulance calls in the city, draining resources that could otherwise be used to create a more equitable city.

These beautiful neighborhoods that were redlined last century are now experiencing some of the hottest temperatures in Richmond.

Whiter parts of town tend to be cooler due to the fact that they have more trees, which also means better air quality. Air quality has a direct impact on health outcomes; during the pandemic, studies demonstrated that people living in neighborhoods with more air pollution had worse health outcomes from Covid-19. Food apartheid also has correlations to redlining, with some of these same historically redlined communities in Richmond having less access to healthy food and local produce. The decisions that have been made by the federal government have a direct impact on current generations and the positive or poor health outcomes.

Redlining, says seedkeeper and farmer Amyrose Foll of Virginia Free Farm, “was a pernicious practice that conveyed the warehousing of people in subpar places” and “took its notes from the same system put in place to warehouse Indigenous people on reservations, removed from their land, environment, and foodways.”

At the same time that redlining diverted investment from communities of color, local and federal officials colluded to create and enact policies that prevented people of color from buying homes in other communities and neighborhoods. The resulting disparities are being felt to this day, and evidence continues to grow about how redlining has poorly impacted communities throughout Virginia and across the country. Redlined neighborhoods in Richmond and Roanoke, like in cities across the US, were the first ones targeted for “urban renewal” projects, where buildings were torn down and some neighborhoods were cut in half by interstate highways, often leading to business closures—and adding more pavement. Research shows that when communities have access to green space and tree-lined streets, their health outcomes improve, from mental to physical health. The psychological effects of living without green space can be striking.

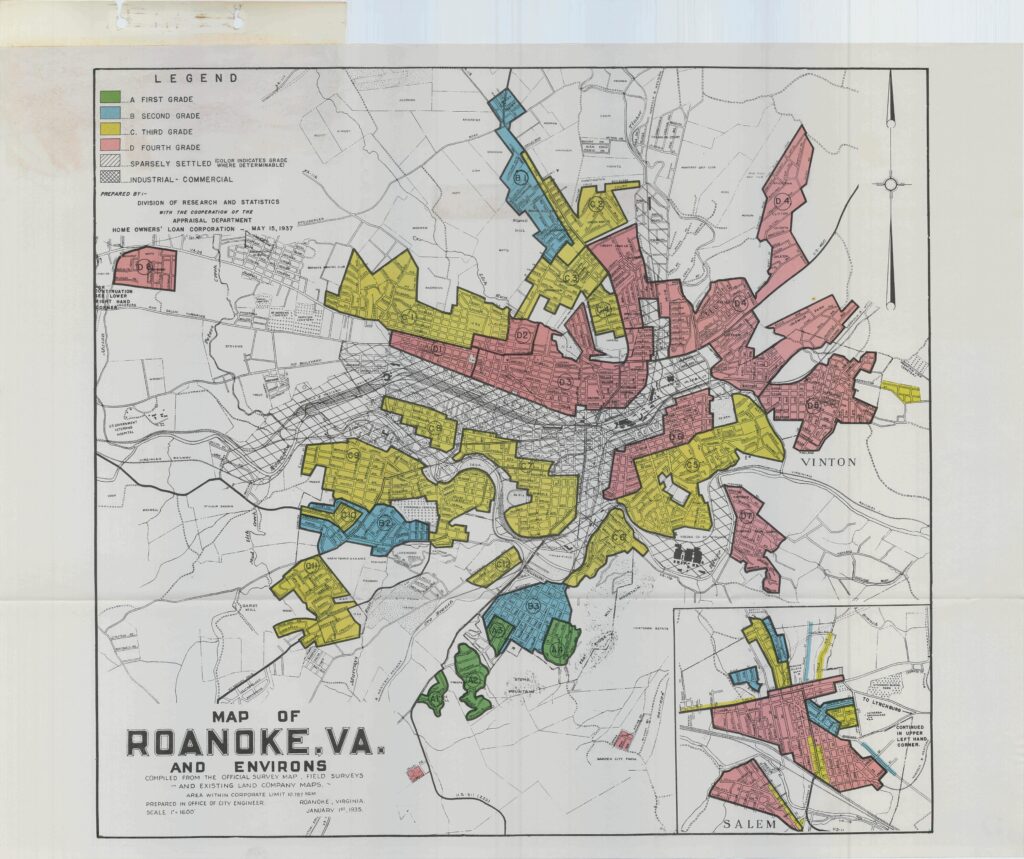

Global warming will increase temperatures in cities around the world, especially during the hot summers of the South, which have a direct impact on many residents in Richmond and Roanoke. In recent years, researchers have been taking a close look at how historical practices like redlining are creating health implications today. In the federal government’s Home Owner’s Loan Corporation’s (HOLC) system for ranking neighborhoods, Black communities were rated as “hazardous,” which meant that they would not have access to federal funding for mortgage loans and were often refused loans from private banks as well. Federally backed mortgages and other lines of credit were not available to these communities, which therefore created a cycle of disinvestment. Researchers at the University of Richmond, Virginia Tech, and the University of Maryland created digital maps of the redlining maps that were used by the federal government, and other researchers have found a recurring pattern of a heat increase in those neighborhoods.

Today, historically redlined neighborhoods are five degrees hotter in the summer than other neighborhoods, with some redlined neighborhoods in Roanoke seeing differences as high as a 10 degree difference and some in Richmond 16 degrees hotter than neighborhoods outlined in green on the old HOLC maps. Communities that did not have access to federal mortgage funding are more likely to be lower income, and to still be predominantly people of color, with fewer trees and parks which allow for a cooling of the air. These communities also have more pavement and nearby highways, which increase the heat and air pollution.

Racism was part and parcel of the appraisal process as loan and insurance companies mapped out these cities during the 1930s. Using a federal program that was designed to help rescue the collapsing housing markets across the county. Neighborhoods of color were designated in red and stated as hazardous, which meant that they could not have access to the federal housing loans that were available at the time. Many of the notes of the appraisers mentioned race as a defining factor in giving out the lowest grades to the areas that had the highest concentrations of people of color.

Neighborhoods of color were designated in red and stated as hazardous, which meant that they could not have access to the federal housing loans that were available at the time.

White homeowners were labeled by the appraisal process as respectable and were outlined in green and blue, and were selected and promoted for federal funding for housing loans. This practice segregated neighborhoods and allowed for some communities to thrive and prosper while others were left to decline, deepening the racial inequality and strife in cities across the country. While white families were easily allowed loans along with other federal assistance to buy homes, allowing them to build wealth for future generations, families of color were denied that opportunity for building wealth that could be passed on generationally. Today in the US, the average white family has nearly ten times the wealth of the average Black family.

Cities like Richmond and Roanoke are now called upon by their communities to create the change that is needed within by confronting the long and robust historical legacy of redlining and drawing into a new future of collaboration and honesty regarding local and federal policies. To address the warming global temperatures and how redlining created an even more additional health burden to communities of color, new approaches and land use practices are needed.