by Vanessa García Polanco

In many of my roles as a food, agriculture, and natural resources practitioner, student, and researcher, I have noticed my uniqueness in the spaces to which I was aiming to belong: nonprofits, higher education research offices, federal offices, agricultural advocacy groups, food policy councils, and others. I was often the only woman of color, the only immigrant, and the youngest person in the room. A lack of diversity in these fields was very apparent. This motivated me to work towards making traditionally underrepresented individuals in these fields more visible, starting with me.

There have been a few exceptions to this loneliness, like attending the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group Conference People of Color Caucus, The Rural Coalition winter forum and most recently, the Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources and Related Sciences annual conference, and being surrounded by people who look like me. But not all food, agriculture, and natural resources spaces and organizations are the same. Food, agriculture, and natural resources organizations and their products and programs are sometimes classified as conventional or alternative.

There has been an explosion of research that decries the negative consequences of conventional food and agriculture systems and a call for eaters to return to more localized consumption practices or what some advocates call “slow food.” This mainstream promotion of an alternative sustainable, local food system is well illustrated in the work of Michael Pollan, Marion Nestle, Wendell Berry, and the mother-daughter team of Anna Lappe and Frances Moore Lappe. The call for alternative food and agriculture systems was also developed as a response to the social inequities that have emerged from the increasingly globalized, conventional food systems throughout the 20th century. In response, organizations such as food policy councils, higher education research organizations, cooperative extension, nonprofit, and broad networks of for-profit and not-for-profit entities formed to support the development of these alternative food systems. The call for inclusion, diversity, and racial equity in the alternative food system movement of traditionally underserved individuals such as people of color, refugees, and immigrants has more recently emerged as an essential goal and priority towards building a just and sustainable food system.

In light of nascent efforts and calls for inclusion and diversity in conventional agriculture, food, and natural resources organizations, and corporations, can these organizations really implement meaningful diversity and inclusion initiatives without a racial equity focus?

Applying a racial equity lens means considering race, structural racism, and discrimination while analyzing and addressing problems, looking for solutions, and defining success. Meanwhile, diversity and inclusion programs across conventional food, agriculture, and natural resources spaces, institutions, and organizations have often prioritized the recruitment and retention of traditionally underrepresented groups in those spaces. Not always do they adopt transformative approaches that prioritize racial equity and the embedded structural racism in their organizations, implementing practices that redesign narratives, programs, services, behaviors related to people of color and other underrepresented groups in these spaces.

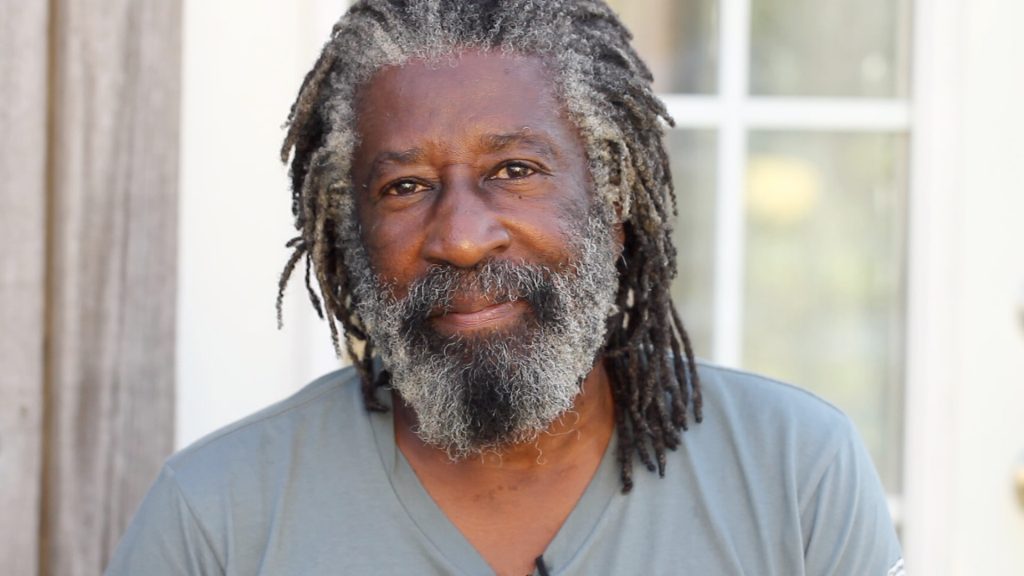

As I reflect on my own current involvement in food, agriculture, and natural resources, and my own experiences now a graduate student, research assistant, and program assistant inside an organization that is attempting to center not only diversity and inclusion but also equity, I’ve found some useful resources. The Continuum on Becoming an Anti-Racist Multicultural Organization measures if organizations are perpetuating hostile and racism environment or taking meaningful steps to transform their organizations towards racial equity. More recently, farmer and food justice activist Leah Penniman identified organizational transformation practices to uproot racism in food and agriculture organizations in her book Farming While Black. These tools have helped me reflect on my own experience at the Michigan State University College of Agriculture and Natural Resources and other organizations I belong to and to understand and work to hold them accountable on a journey towards transformation.

While many food organizations are starting to realize the need to center racial equity and equity as a whole in their organizations, I call upon more organizations educating and fostering the next generation of immigrants, refugees, minorities and all people of color to do so soon, rather than later. In a time when the land ownership of farmers of color is declining and the need for a steady pipeline of the next generation of people of color in food, agriculture, and natural resources is needed more than ever, we need more organizations committed to equity, diversity, and inclusion. Reconnecting and empowering traditionally underrepresented communities to rejoin the agrarian tradition is the goal of many organizations and projects such as Agrarian Trust. But many individuals and organizations wonder where to start. I am happy to belong to the Racial Equity in Food System Working Group, a community of professionals and community stakeholders who connect, learn, and collaborate to facilitate change within our institutions and society to build racial equity within the food system. Spaces and resources like the Food Solutions New England 21-Day Racial Equity Challenge are venues to explore as individuals and organizations to push ourselves beyond diversity and inclusion and towards building a truly just, sustainable, and equitable food system.