If you drive east from Vancouver, BC, for about an hour and a half on a Saturday morning, you can join the group of city dwellers, expats, artists and others gathering for the weekend harvest at Abundance Community Farm. “We call it the farmily,” chuckled Amir Niroumand. He purchased the land for Abundance in 2016 as a place for intentional community and collective farming. It was a risky investment – an experiment in communal responsibility – and it worked. Now, Niroumand is thinking about the future.

“I have no need of selling the land,” said Niroumand. Rather, with the right model, “it can stand on its own, and then it can basically transition to society.” Niroumand believes that by leveraging the community’s skills and expertise, the farm can come to financially sustain itself far beyond him. But how to make the transition?

This is the question that Foodlands’ Your Land, Your Legacy program arose to address. Foodlands is a cooperative out of British Columbia that secures food-producing land for community ownership and stewardship. They created Your Land, Your Legacy to support landowners who are imagining the next chapter for their land, and who want it to continue producing food for their community into perpetuity.

“We’re talking to the people who have put their whole life energy into that land and do not want to see it developed. They have a very strong sense that it’s their legacy to give,” said Heather Pritchard, Foodlands’ founder who has herself lived on a cooperative farm for 36 years.

Pritchard explained that Your Land, Your Legacy is a two-part land donation and transition system. First, Foodlands’ network of financial advisors, will planners, and legal experts work with landowners to set up a model tailored to their wishes.

“It’s as much an emotional process as it is a legal or regulatory one,” said Pritchard, who meets with landowners in their homes to work through the details. “How do they name their legacy? How do they see it?” The program meets landowners in any financial situation, whether they wish to donate their land outright, provide for retirement, or leave something to their children.

Pritchard believes there is no one way to approach land donation, and focuses on the needs of the individual. “What do you need for the 30 years of energy that you’ve put into this, often with very little pay, to create a beautiful, productive farm? What is fair?” By asking these questions, Foodlands helps landowners look beyond the monetary value of their land. Together, they create a plan that allows landowners to give both generously and comfortably.

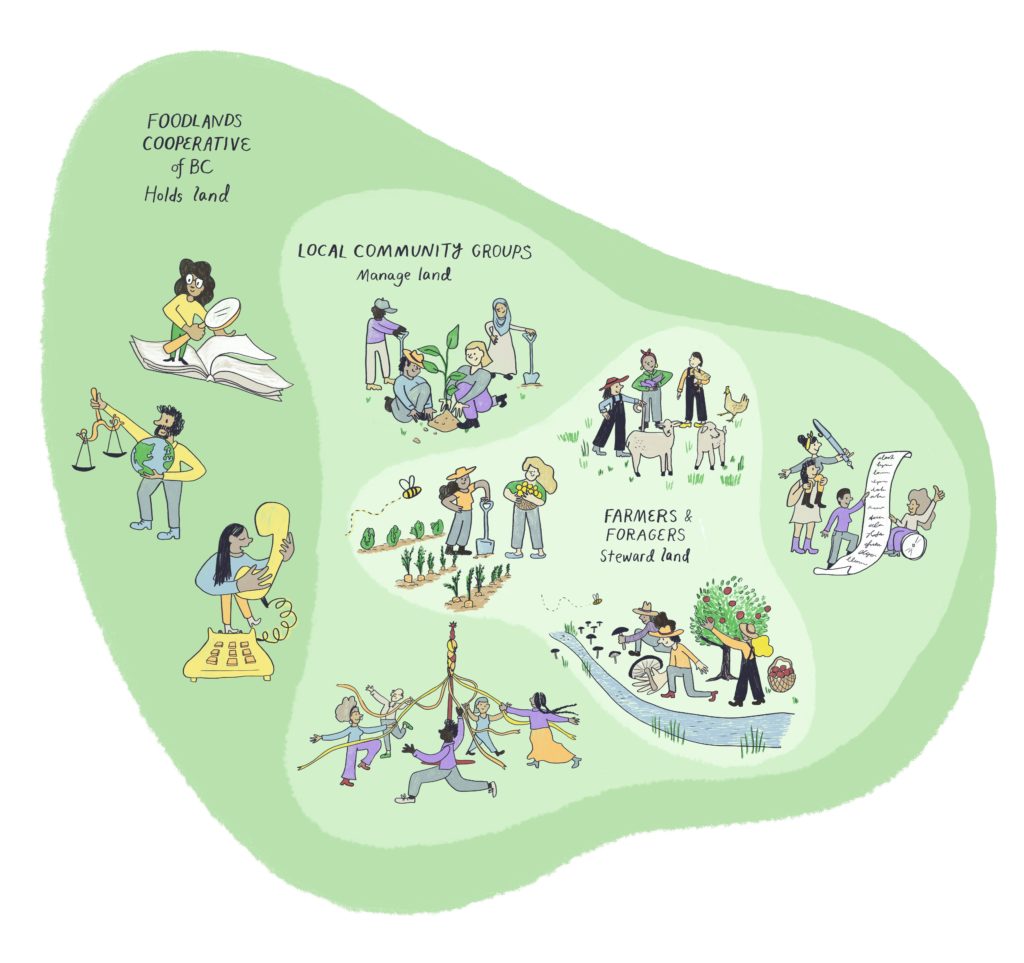

The other half of the program involves making the land accessible to the public through a community management model. Foodlands leverages its network of producers and organizations to identify a community group that will take on responsibility for the land. Once a group is formed, Foodlands helps them define their values and purpose, and supports them in the creation of a cooperative.

“Very deeply part of what we would do is to make sure that people are understanding their relationship to the land in terms of it being unceded territory,” said Pritchard. Beyond removing arable land from the speculative market, one of the cooperative’s foremost objectives is to foster shared ecological stewardship that respects and includes Indigenous food systems—in other words, to decolonize land. Pritchard explained that this work has a lot to do with how communities position themselves in relation to the land they tend. “If I ever would have a goal, it is to decommoditize. To really see it as sacred,” she said.

With the terms defined and a community group in place, Foodlands connects the landowner with a charitable group able to receive the land. At this stage, Foodlands employs its Land Transfer Legal Literacy Project to walk all parties through the transfer of land into trust. And still the job is not done. The cooperative will continue to support the transition of the land and the community that will steward it into perpetuity.

As landowners, charities, and communities work with Foodlands through this process, the organization continues to build a robust network of producers and organizations, all working toward the mutual end of a more just and resilient food system, local to BC.

For Pritchard, the need cannot be overstated.

“All across the world, communities are food insecure. And food security will only happen when there is food provisioning close to home, when those who want to engage in providing for their communities are able to cultivate the land, forage, or wildcraft,” said Pritchard. “You can only do that if [farmers and foragers] have some kind of long-term tenure.”

Foodlands formed to meet this need in British Columbia, where low tax rates, pristine landscapes, and political stability have created the perfect conditions for a burgeoning global property market. Development pressures are high even on protected land, and those committed to regenerative farming are relegated to short-term leases.

But for Niroumand, Foodlands’ commitment to ensuring long-term land tenure could help him realize a future for Abundance Community Farm that extends far past a several year lease. He envisions his community growing through multiple generations.

“One of the beauties here that touches me most of all is seeing kids relate to the world in a different way. They’re roaming freely on a farm, they’re in a community they trust,” said Niroumand. “For me, this place is about them. I want it to be here for them.”

The Foodlands Cooperative of BC (Foodlands) is a community service cooperative founded in 2017 with the mission to secure land in trust and promote the protection and stewardship of food providing lands across BC. Foodlands works with landholders, farmers, local communities and leaders in the agricultural and land trust sectors to develop and support community foodlands models and build healthy, local food systems.