First, what does it mean to be involved in the Agrarian Commons? And what is your role in the West Virginia Agrarian Commons?

I serve as a board member of the West Virginia Agrarian Commons. In that role, I help guide the Commons’ core mission of “land commoning.” That means converting land into “commons” that is accessible for agrarian uses that benefit everyone, and counterbalancing the rent-seeking uses that devalue our land and dispossess our people, who rely on the health of land and water.

My college advisor was Professor Brian Donahue at Brandeis University. He is a truly visionary proponent of expanding the agrarian commons across America. He inspired me to see the value of this work and to support it throughout my life.

The tagline for your law practice is “Fighting for Workers in the Heart of Appalachia.” How do you represent workers? What are some of the kinds of cases you take on? And what drew you to this kind of work?

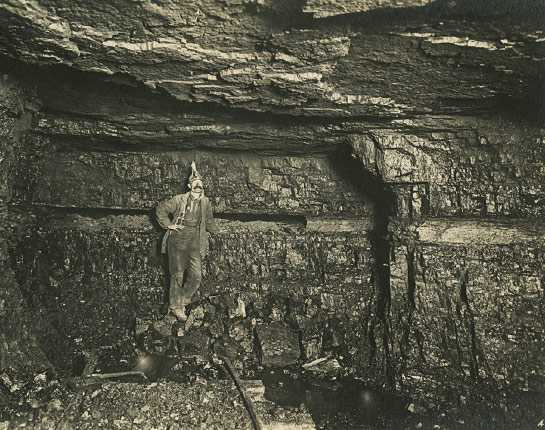

My clients sue mostly coal companies, but also other large employers, who we believe are violating the law by failing to pay adequate wages and benefits to workers and retirees. We also file safety grievances against coal mine operators to reduce the risks of workplace accidents and black lung disease. There has been a deadly resurgence of black lung disease sweeping across Central Appalachia over the past two decades as coal companies cut through larger amounts of toxic silica-bearing sandstone to access the dwindling amount of thin-seam coal reserves that still remain in the heavily depleted Central Appalachian coalfields.

There has been a deadly resurgence of black lung disease sweeping across Central Appalachia over the past two decades as coal companies cut through larger amounts of toxic silica-bearing sandstone to access the dwindling amount of thin-seam coal reserves that still remain in the heavily depleted Central Appalachian coalfields.

My work helps to create an extra measure of economic agency for workers to pursue the professional and vocational futures that seem best for their families and the broader community.

The stereotypical picture of Appalachia, and coal mining, is a picture of white Americana. How accurate is that to the workers you represent and coal miners in the region historically?

Inaccurate stereotypes have long menaced Appalachia. The truth is that diversity plays a central role in both our historical and current identities, yet we still struggle with systemic racism, as in many places. There are many mixed families in Appalachia—racially, ethnically, and religiously. Slave labor developed some of the earliest mines in our region, and we have strong African American communities. Immigrants from across the globe played a central part in expanding the mining business throughout the twentieth century, bringing customs, festivals, and foods that suffuse Appalachian culture today. According to a study released in January 2017 by the Williams Institute, West Virginia has the highest rate of transgender teenagers out of all fifty states. Trans miners face heightened risks of discrimination in the underground work environment.

Last fall, you represented a surface coal miner who’d been wrongfully fired after complaining about unfair work conditions in Wyoming County. What led you to take on this case, and what do you think persuaded the jury to decide in favor of your client?

My client in that case complained about unsafe blasting techniques and refused to perform unsafe welding on large mining machines that are used in the surface mining practice known as mountaintop removal. When mining companies cut corners on safety, it harms the workers, the land, the water, and the broader community. Our jury system enables members of local communities to draw the line when companies go too far for the sake of the almighty dollar.

When mining companies cut corners on safety, it harms the workers, the land, the water, and the broader community.

You also have a personal connection to Wyoming County, having been an Americorps*VISTA worker there. Is there anything unique about the county, from a cultural, geographic, or economic perspective? Also, what was your VISTA program, and did it play a role in the direction of your career?

The people and land of Wyoming County are near and dear to me from my service there as a community development VISTA worker and my life’s work representing citizens there and in surrounding counties. Wyoming County is one of numerous counties across our state where essentially all the land and minerals are owned by a couple out-of-state corporations that acquired the land at fire-sale prices back when the railroads first came through to develop the coalfields. West Virginia country star Brad Paisley sings about this process in “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive,” written by Darrell Scott. The land companies are essentially speculators that don’t pay their fair share of taxes. They rake in massive profits at the expense of our land and the labor of our people. This dispossession of people from land causes underfunding of essential government services, and it is the fundamental source of the crippling poverty that emanates across our society in West Virginia, as in many mineral-producing regions across the world. My education on these matters as a student and a VISTA worker has informed my perspective greatly.

How does your work on addiction and recovery tie in to your advocacy on behalf of laborers? Were there any personal or social experiences that inspired you to take a more open, supportive view of recovered addicts or even addicts themselves?

The addiction crisis is more pronounced in communities like those in West Virginia because many people in these communities lack adequate health insurance and healthcare facilities to properly treat orthopedic injuries or to access better, costlier, non-pharmaceutical methods of healing, such as early MRIs, surgery, and physical therapy. Under pressure from the coal and mineral interests, the state privatized workers’ compensation in 2004-2005. This left many injured workers with inadequate coverage, such that one of the most common treatments provided for workplace injuries was unhelpful opioid analgesics—a problem that persists today. This has compounded the background problem of systemic poverty and lack of health insurance in the general population, creating a perfect storm for drug diversion, substance use disorder, and the massive social catastrophe that has unfolded here in recent decades.

According to the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the two biggest barriers to success in long-term recovery from addiction are: 1) stigma of being in drug treatment programs, and 2) unaffordability of treatment. I have written and taught extensively on the obligation of employers to destigmatize addiction in the workplace and to provide affordable and flexible treatment options for workers. The workplace is a central part of our lives, and it contributed to this crisis in West Virginia through the privatization of workers’ compensation. The workplace can and must play a similar role in surmounting these barriers to success with long-term recovery. That is why I focus on these goals in my advocacy.

Why should readers support the West Virginia Agrarian Commons?

The Agrarian Commons is building a publicly accountable, nonprofit treasury for the purpose of returning land into the hands of the people for sustainable development. This is the most fundamentally transformational work that can occur to rebalance social inequities and to realign the systemic root of economic injustice in West Virginia and anywhere that land dispossession has occurred.

Sam Petsonk has spent his career challenging injustices in the courts and the legislature, and has won game-changing results for countless workers across West Virginia and Appalachia. In 2013, he received the prestigious Skadden Fellowship to launch the Miner Safety and Health Project at Mountain State Justice, a nonprofit legal services program representing underserved West Virginians. Sam’s legal work has secured millions of dollars in wages and benefits for coal miners and other workers across West Virginia, and assisted thousands of miners following layoffs in the coal industry. In addition to his legal work, Sam is engaged in various community and economic development projects. He lives with his wife and two sons in Fayette County.