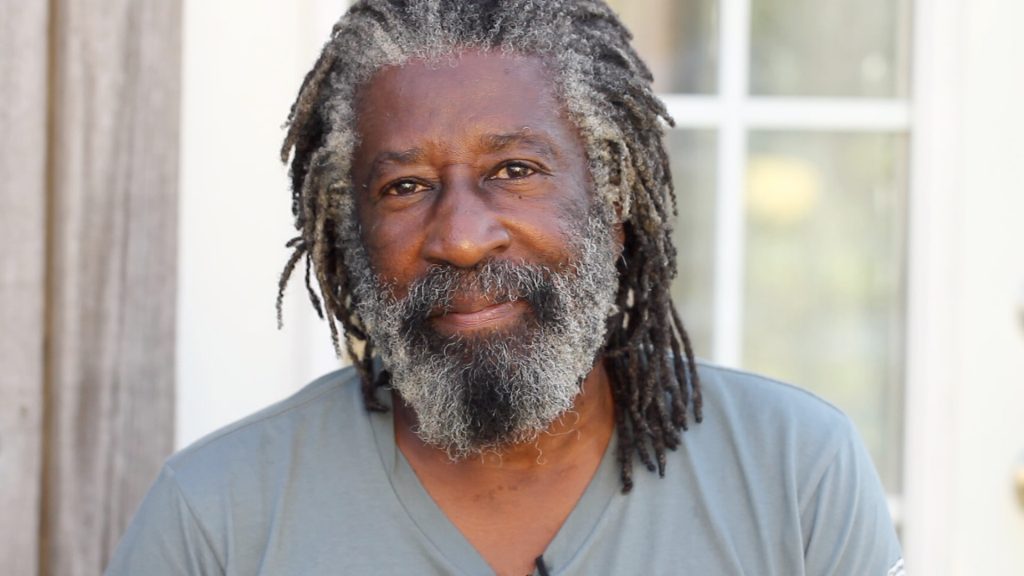

A Q&A with Renard Turner, co-owner and operator of Vanguard Ranch and founding board member of the Central Virginia Agrarian Commons.

What drew you to the Agrarian Commons? How does the Commons model tie in to your vision for agriculture in Central Virginia?

My work as a member of the Community Ownership Empowerment and Prosperity team revolved around food justice issues. Central to any food justice discussion is the issue of land accessibility. Historically, land ownership and access in America has been highly restrictive and even hostile to all non-white persons. The Agrarian Commons concept offers an alternative vision of collective and shared intentional land use that challenges the historical norm by offering 99-year leases to persons interested in engaging in holistic agrarianism lifestyles. I would like to see the development of several Agrarian Commons sites in central Virginia promoting African American involvement in vocational agriculture, as producers of agricultural goods and services.

Describe your journey as a farmer. What personal, social, and/or cultural factors have shaped your experience and decisions?

I have been interested in agriculture since my high school years in Fairfield, California.

I was born into a US Air Force military family. As a direct result of that, I had the opportunity to attend schools which were much better funded and therefore better equipped than the traditionally segregated inner city school systems that most African American children are subjected to. I had excellent instructors in high school and took agricultural science and engineering classes, excelling in both. Exposure to vocational agriculture was a serious eye opener. Understanding how food is grown and where it comes from gives a person a totally different perspective.

As I grew older it became obvious to me that many of the social injustices that black folks still are subjected to come from systemic racism and especially the inability to own, control, produce, and deliver food and food products to the black community. Heritable land transferred wealth to whites intergenerationally—and it still continues on today. People of color are left out of that equation.

I farm as an act of liberation. I am a land steward intent on making positive changes for a greener, more egalitarian agrarian world.

You raise kiko goats, a unique heritage breed of meat goats. Another unique aspect of your business is that you sell prepared goat meat, what is known in the farming world as “value added production.” How did you land on this approach to sales? Any lessons here for other small-scale farmers?

I did start with Kiko goats, we now raise Myotonic goats and have developed our own line named BANGUS. We are a small family farm. Economy of scale dictated that the only way to have a chance was to go value-added. We purchased a concession trailer, got a restaurant licence, and took our goat meat to the public as ready-to-eat meals. We pioneered the Original Vanguard Ranch Hickory Smoked goat burger, goat kabobs, and curried goat. The intention was to retain more value in the form of cash from our production versus allowing the middle man to buy from us cheap and sell high. We only sold our product on a plate or as breeding stock. I strongly suggest that all small farm operators seek value-added as the way to go. It takes some tenacity and risk, but building your own brand is best.

What is your philosophy as a land steward? Can you share some of your strategies in tending the land? How does your approach differ from conventional farming methods?

We have always been and always will be naturalists. We are sustainable, organic, and regenerative in all we do on the farm. We use no conventional chemicals, never overstock, rotate pastures, and allow native vegetation to show us what is conducive in our microclimate. We use drip irrigation and ground covers in our produce production spaces. We use a high tunnel to extend our growing season. We focus on heirloom vegetables and ethnic produce. It is important to let the land rest for a season and regenerate. We know that promoting good microbes in the soil is the key to healthy farms and people.

You’ve observed that rural Black farmers are borderline invisible—sometimes even to urban BIPOC communities—and continue to lose their land at an alarming rate. How has the loss of farmland impacted Black communities in your region?

Black folks continue to lose land at an alarming rate of 30,000 acres per year! We now own less land than we did in 1935! The usual concept of a black community is centered around the urban black experience. Black farmers are not a new-age concept. The sad reality is that most black folks continue to know little about vocational agriculture.

What would you like more people to know about the present and the history of Black farmers in the US and in Virginia in particular?

We are still here! We need customers! We were pivotal in the development of America. Agricultural skill sets came with enslaved Africans. These skills contributed to the wealth of others. Booker T. Whatley, a black man, is the forerunner in sustainable agriculture—but few know of him. Rural independent black farmers continue to struggle with almost no national attention. There is a population of black farmers that are not millennials!

How will the Central Virginia Agrarian Commons enable secure land tenure for Black farmers in Virginia?

We intend to be progressively aggressive in our pursuit of promoting land access for BIPOC folks. My vision is having a network of farmers collectively working to produce foods and food services on an economy of scale that is vocationally viable. Grow it, process it, deliver and sell it.

I hope the Agrarian Commons concept takes root in the black community and vocational agriculture becomes a desirable goal.

Why is support for aggregation and distribution crucial for Black farmers in Virginia?

This is crucial for Black folks across the board. For Black farmers, it is one way to get increased market share. Black farmers need to own the supermarkets in the communities black folks live in.

Why should readers support the Central Virginia Agrarian Commons?

White folks own 95% of all farmland in America. Five white people own more land than all the black folks own together in America. This is not good moving forward—change must come! Let us be mindful as well of our Indigenous brothers and sisters who also have been and continue to be subjected to systemic racism and endure the fact that their land was stolen.

Renard Turner is the co-owner and operator of Vanguard Ranch, a diversified farm business located in Louisa County just southeast of Gordonsville, Virginia. He and his wife, Chinette, founded the business in 2007 on land they had purchased, and have since raised pastured heritage goats and organic heirloom vegetables for sale in local markets in Charlottesville. The goat meat is sold through the farm’s concession trailer, most frequently at live events held in collaboration with breweries and wineries, as well as at music festivals hosted by the Turners on property adjoining their farm.

Over the years, Turner has taken on many leadership positions, including president of the Virginia Association for Biological Farming, national secretary of The American Kiko Goat Association, board member of the Virginia State University College of Agriculture, and member of the Minority Farm Advisory Council under secretary of agriculture Tom Vilsack. He is currently a team member of The Community Ownership Empowerment & Prosperity project of The Chesapeake Foodshed Network.