Republished with permission from The New Farmer’s Almanac (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2019)

by Jean Willoughby and Douglass DeCandia

The cause of reparations is having a moment of resurgence in the United States. Author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates reinvigorated the idea in a sweeping and influential essay, “The Case for Reparations,” published in The Atlantic in 2014. In 2016, after more than a decade of rigorous investigation, the United Nations’ Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent determined that “past injustices and crimes against African Americans need to be addressed with reparatory justice.”1 In the United States, the term reparations is most associated with the idea of compensation for slavery, but the idea has also been explored by Coates and others as an integral part of redressing racial discrimination and injustice in our own times.

When the Movement for Black Lives released its first policy platform in 2016, it reflected a demonstrated consensus built among more than fifty organizations across the country. The platform is notable for its demand for reparations “for past and continuing harms” wrought by “government, responsible corporations and other institutions that have profited off of the harm they have inflicted on Black people—from colonialism to slavery through food and housing redlining, mass incarceration, and surveillance.”2 In a related vein, House Resolution 40, the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, has lately gained increasing attention from social justice groups and the media. Specifically, HR 40 would “examine slavery and discrimination in the colonies and the United States from 1619 to the present and recommend appropriate remedies.”3 Introduced in each session of Congress since 1989, the bill has never garnered enough votes to make it to the floor for debate. Both despite and because of this inertia, Coates described the bill as the vehicle for a national reckoning that is long overdue.4 In their platform, the Movement for Black Lives calls for its immediate passage.

In 2018, a group of farmers of color and organizers based at Soul Fire Farm in New York launched the online Reparations Map for Black-Indigenous Farmers. Calling for “reparations of land and resources so that we can grow nourishing food and distribute it in our communities,” the organizers assert that our “food system was built on the stolen land and stolen labor of Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Asian and people of color.”5 Their map shows projects of farmers of color across the country and lists the resources these farmers need for development and growth. The map’s organizers encourage “people-to-people solidarity” in meeting these needs and view the endeavor not only as a method for increasing the self-determination of communities of color but also of providing an anchored source of connection and healing in people’s everyday lives.

These efforts are powerful, instructive examples of individual and collective action. As advocates working for a just, equitable, and life-affirming food system, the authors of this essay have spent much of the past year reflecting on the power of reparations to remake this land that we can’t help but call home. We come to this work as two white people who have each spent the past decade involved in sustainable agriculture. One of us works as an agricultural educator and grower with a food bank. The other works as an advocate and strategist in farmland preservation, developing models of land stewardship that expand on the principles and practices of community supported agriculture. Both of us enjoy connecting with other people in relation to the land and the sources of our daily sustenance. Antiracism work and community organizing also play strong roles in our professional and personal lives. We’re both drawn to farms and gardens, fascinated by agriculture as a nexus between nature and humanity, and here we consider the rationale for reparations and the role they could play in our food system.

A Brief Look at Racism in the Food System

Many of the ways that racism shapes our food system can be summarized in the word access—lack of access to food, to farms and farmland, to agricultural and business lending, and to the fundamental needs for clean air, water, and soil. Statistics on race and the food system mirror what we observe about racism across all systems in our country: that is, white people typically experience better outcomes than any other racial group, while black people experience some of the worst outcomes. In states with larger populations of Native Americans or Latinos, those groups typically experience some of the worst outcomes, but the pervasive pattern remains. Regarding food access and health, studies have shown that, on average, black households are significantly less likely to live near a supermarket than are white households and that supermarket inaccessibility corresponds with higher rates of obesity. Fresh, unprocessed food is out of reach for many black families whose neighborhoods are often surrounded by fast food chains and corner stores that offer cheap, calorie-dense meals and snacks.

Cheap food exacts a high price. The negative effects of unhealthy diets can be felt in all communities, but they are particularly pronounced and alarmingly fatal among groups who have been dispossessed and displaced from their land or community. Numerous scientific studies have found that high rates of diet-related illnesses such as heart disease and type-2 diabetes disproportionately affect black Americans—typically at rates two to three times higher than white Americans. Epidemiological research has also shown that displaced indigenous people, not only in the United States but around the world, often experience skyrocketing rates of these same illnesses in the years and generations following their dispossession and displacement.6

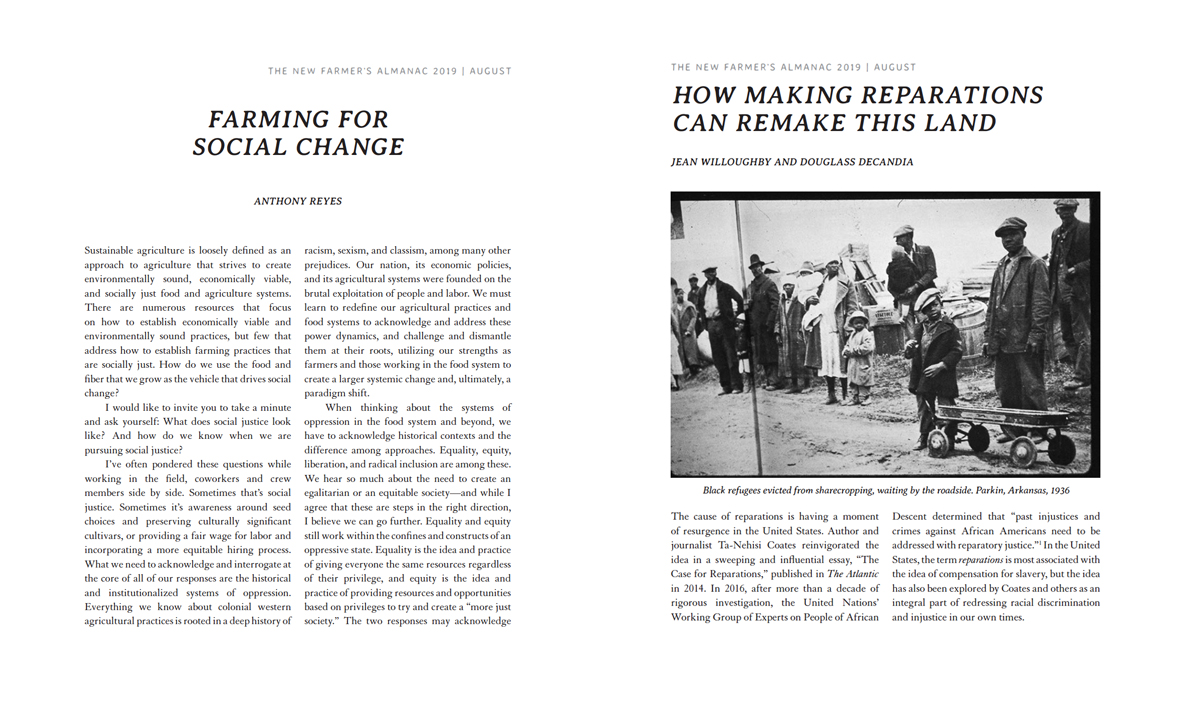

The taking of land from communities of color in this country of course does not end with indigenous people. In his book Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights, historian Pete Daniel gives a damning account of the discrimination experienced by black farmers at the hands of the US Department of Agriculture. Between 1940 and 1974, the number of black farmers plummeted, from 681,790 to 45,594, a 93 percent drop within a single generation.7 Daniel notes that in the early 1970s, legal observers predicted that a fierce and protracted battle of lawsuits, lobbying, and organizing would be necessary to break the stranglehold of discrimination within the USDA. They were right.

Daniel’s book provides more than ample explanation for why black farmers would ultimately turn to the courts. In 1999, the US government entered into an agreement with a group of black farmers in the Pigford v. Glickman case in what was and may still yet be the largest civil rights class-action settlement in US history. In short, the farmers sued the USDA for racial discrimination and won. The majority of the funds consisted of $50,000 payments to 33,256 individual black farmers or their heirs. Unfortunately, the payments received were typically not enough to restore the land and farms lost to them years before.

Land Ownership and the Racial Wealth Gap

Scholars and journalists rightly focus on the pivotal relationship between the federal government and the housing market in creating and maintaining the modern racial wealth gap. But wealth obtained from ownership of America’s farmland is also a significant contributor. Today, between 95 and 98 percent of all farmland in the United States is owned by white families. This is no accident but rather the outcome of hundreds of years of public policy advantaging white people over people of color in both the right and the opportunity to own land.8 Accounting for 40 to 50 percent of all the land within our borders, the farmland owned by white families is estimated to be worth more than $1 trillion. And while more than 90 percent of farm owners and operators are white, farm labor is another story. Surveys over the past decade have consistently found that around 80 percent of farmworkers identify as Hispanic or Latino, with the majority born in Mexico.9 We have now an essentially racialized food production system comprised of white owners and brown workers.

According to recent research, the racial wealth gap is widening. The US Federal Reserve found that white families have the highest median net worth: $171,000. Black families’ median net worth is less than 15 percent of that: $17,600. Hispanic and Latino families’ median net worth is $20,700. The gap also persists across the lowest income levels: White households living near the poverty line nevertheless typically hold around $18,000 in wealth (often based on assets such as cars or real estate), while black households earning similarly low incomes typically own little to nothing that an accountant would classify as a valuable asset.10 Furthermore, median black and Hispanic-Latino wealth appear to be declining. The nonprofits Prosperity Now and the Institute for Policy Studies have projected that by 2053 the median wealth of black families could hit zero.11 Hispanic-Latino families are expected to drop to the same level by twenty years later.

In light of these alarming trends, a collaboration of scholars at Duke University’s Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development made a bold and decisive statement, declaring that there are “no actions that black Americans can take unilaterally that will have much of an effect on reducing the racial wealth gap.” In their comprehensive report, they concluded that “addressing racial wealth inequality will require a major redistributive effort or another major public policy intervention.”12 To accomplish this, they suggest the creation of a reparations program to compensate black Americans for the intergenerational impact of slavery and legal discrimination or “the equivalent of a substantial trust fund for every wealth-poor American,” noting that the two approaches need not be mutually exclusive.

Making Amends

Reparations can be simply defined as making amends for past wrongs. It’s generally understood as a practice of making some form of payment with the goal of ameliorating the living conditions of those harmed. Payment is where the discussion over reparations tends to get stuck. Figuring the math of reparations can easily consume any discussion of the subject. For all their serious commitment to seeing the numbers work, those who focus the conversation on debating methods of calculation and distribution tend to miss its point.

Reparations has alternatively been discussed as a kind of moral accounting. Coates relies on this metaphor in describing America’s “compounding moral debt.” Our nation’s moral “credit-card bill” keeps growing, he writes, and though we’ve “pledged to charge no more … the effects of that balance, interest accruing daily, are all around us.”13 Though the true cost of righting past wrongs will forever remain incalculable, scholars insist that it is very possible to estimate the financial impact of discrimination against people of color, particularly black people, locked out of housing markets, education, health care, and other resources more readily available to white people. But the work of reparations encompasses far more than the practicalities of the redistribution of resources, the repayment of benefits, or the repatriation of land.

Countless people have justifiably questioned whether a price could ever be put on the defining tragedies of our nation’s history: genocide, slavery, dispossession, discrimination. The answer, of course, is no. Nevertheless, the act of making reparations would constitute a profound and unprecedented acknowledgment of the lasting effect of past wrongs and a visionary commitment to an equitable society, to liberty, and to justice. It would speak to an understanding, a reckoning that stretches well beyond our usual reach of moral accounting.

Despite criticisms that reparations dwell on the distant past, the work of reparations is made on behalf of the present and the future.

Calculating the dollar amount owed to the people who have been wronged by our country will not necessarily compel us to give it. Indebtedness alone will not move us toward reconciliation, nor will morality alone. Knowing how much we’re all still losing because of racism and our legacy of racial inequity might. To have the will to make reparations our reality, we will have to understand what our inequity is costing us, individually, in our communities, and as a nation.

In financial terms, we now know that the cost to the country is tremendous: nearly $2 trillion. A 2013 study from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation and researchers from Brandeis, Harvard, and Johns Hopkins Universities found that the United States loses trillions in “lost earnings, avoidable public expenditures, and lost economic output” due to the economic impact of racial inequity. They found that if the average wages of people of color were made equal to those earned by whites, overall earnings in the United States would increase by 12 percent, for a total of nearly $1 trillion. By closing this gap in earnings, the authors projected that the total value of our country’s economic output would increase by $1.9 trillion.14

Building Trust

Many people distrust the idea of reparations. For some, that may have more to do with lack of trust in our government than the idea itself. Undoubtedly, many people are genuinely uncertain about the full basis for its claim and its potential implications. This makes the passage of a “study bill” like HR 40 critical for increasing public knowledge and confidence. In the broader context, it’s also important to take into account the impact of race and racism on public trust. “Race is the life experience that has the biggest impact on trust,” according to political scientist Eric M. Uslaner.15 His work points to significant racial “trust gaps” that recall gaps in areas like wealth and education. Even where well-founded, a lack of trust can inculcate cynicism, apathy, and hopelessness in our interactions with government, institutions, and other people. A lack of trust weakens social bonds and can cause us to retreat from public life and political engagement. And, unsurprisingly, racism damages public trust in a multitude of ways. For our discussion, it’s important to consider that a lack of public trust can undermine support for publicly funded initiatives and make it less likely that the public will engage in efforts to redistribute power and resources.

In the past, calls for reparations that have managed to attain a popular audience haven’t translated into sustained momentum. But there is reason to be hopeful. Millennials appear to be significantly more open to considering reparations than past generations. A Marist poll suggested that more than half of millennials are willing to consider the idea of reparations for slavery: 40 percent of millennials came out in favor of reparations while 11 percent were unsure. The conversation about reparations will continue to develop as the most diverse demographic in US history takes a place at the table.

Despite criticisms that reparations dwell on the distant past, the work of reparations is made on behalf of the present and the future. Disparities of wealth, land and property ownership, and access to resources are ultimately harmful to all of us and, if not reversed, will have a destructive impact on the world the next generation grows up in too. Making reparations is part of our work toward collective liberation from the social ills caused by inequity. In this context, sharing and redistributing resources is an act of solidarity, not simply an attempt to repay an unpayable debt. The call for reparations seems best understood not just as a request or demand for a compensatory payout, but as part of an ongoing, collaborative effort that moves us further toward ending racial inequity and racism.

Many groups presently organizing in support of reparations have embraced the need to build trust and relationships between and among people of color and white people. This is no small endeavor. Organizing cross-racially and building our solidarity on shared values allows us to model the world we want to create, cultivating a sense of belonging and connection. By supporting the cause of reparations, those who have gained an advantage from racism can take part in dismantling this unjust system.

Reparations on the Land

Agriculture is a profession in which our values and decisions are written on the landscape. As agrarian organizers, we want to cultivate an agriculture that reflects our commitments to sustainability, biodiversity, cooperation, and fairness—and that embraces creative and effective strategies to get us there. In rural America, reparations might find expression on the land though the legal restoration of land, bequests, gifts of land, grants, community supported farming initiatives that respond to the needs of farmers of color, and other reparatory efforts undertaken by landowners.

We’re curious about how we can step up to support these kinds of efforts in farming communities. At present, we have more questions than answers: How can communities organize and come to a consensus on taking action for reparations? How can institutional landowners be engaged and involved? What are some of the ways that entities like towns and cities, religious institutions, companies, nonprofits, land trusts, and universities can participate in dialogue with their constituents and communities around these questions? And how can we, as gatekeepers within our groups and institutions, achieve accountability and reparatory justice in the ways resources such as land and space are allocated and accessed?

As community organizers, we want to ensure that dialogue and inquiry lead to action and reconciliation. By collaborating with reparations efforts nationally, it’s possible to share what’s working and gain exposure to different approaches. As relevant initiatives continue to emerge, many seem designed with the next generation of reparationists in mind. Innovative tools like the online reparations map and the Native Land app are bringing heightened visibility and the power of the internet to centuries-old struggles. The many reparatory justice groups active on social media are connecting people who wish to practice reparations through posts of “requests” and “offerings” that can be shared or amplified by others. Social justice groups that organize among young people with wealth are fundraising for organizations led by people of color both as a form of reparations and as part of their long-term strategy to end racial inequity. With each advance, activists and organizers are developing the resources and capacity to write a new chapter in the long history of the movement for reparations. It may be that the liberation we seek is already being traced on the land.

Notes

1. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Statement to the Media by the United Nations’ Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, on the Conclusion of its Official Visit to USA,” January 2016. www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=17000.

2. The Movement for Black Lives, “Reparations,” https://policy.m4bl.org/reparations.

3. US Congress. House. Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act. 115th Congress. Introduced January 3, 2017.

4. Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014.

5. Soul Fire Farm, “Reparations: Reparations Map for Black-Indigenous Farmers,” www.soulfirefarm.org/support/reparations.

6. California Newsreel, Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick? San Francisco: California Newsreel, 2008. www.unnaturalcauses.org.

7. Pete Daniel, Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013).

8. Howard Zinn. A People’s History of the United States. (New York: Harper & Row, 1990).

9. Trish Hernandez, Susan Gabbard, and Daniel Carroll. “Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey 2013-2014: A Demographic and Employment Profile of United States Farmworkers.” U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration Office of Policy Development and Research, December 2016, https://www.doleta.gov/agworker/pdf/NAWS_Research_Report_12_Final_508_Compliant.pdf.

10. Lisa J. Dettling, Joanne W. Hsu, Lindsay Jacobs, Kevin B. Moore, and Jeffrey P. Thompson. “Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 27, 2017, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2083.

11. Chuck Collins, Dedrick Asante-Muhammed, Emanuel Nieves, and Josh Hoxie. “The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide Is Hollowing Out America’s Middle Class.” Prosperity Now, September 11, 2017.

12. William Darity Jr., Darrick Hamilton, Mark Paul, Alan Aja, Anne Price, Antonio Moore, and Caterina Chiopris, “What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap,” Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development, April 2018, http://goo.gl/SJJyLo.

13. Coates, “The Case for Reparations.”

14. Ani Turner, Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, Darrell Gaskin, Thomas LaVeist, David R. Williams, Laura Segal, and George Miller. “The Business Case for Racial Equity.” W.K. Kellogg Foundation and Altarum Institute, October 2013, https://www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2013/10/the-business-case-for-racial-equity.

15. Eric M. Uslaner, The Moral Foundations of Trust. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002).