From grain.org:

Since the global food crisis of 2008, there has been a massive wave of private sector investment in agriculture. More money flowing into agriculture means more innovation and modernisation, more jobs and more food for a hungry planet, say the G8, the World Bank and corporate investors themselves.

But does it?

Looking at the investments made by Indian billionaire Chinnakannan Sivasankaran – one of the most active private sector players in the global rush to acquire farmland – a worrying picture emerges of what happens when speculative finance starts flowing into food production.

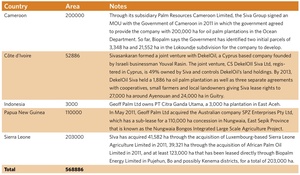

Since 2008, the Siva Group and its myriad subsidiaries have acquired stakes in around a million hectares of land in the Americas, Africa and Asia, primarily for oil palm plantations. On paper, he’s now one of the world’s largest farmland holders.

But Sivasankaran’s also a land grabber and tax avoider. Like the majority of transnational investors in agriculture, his investments are channeled through a web of shell companies based in offshore tax havens. The companies he holds shares in are engaged in dubious land deals and kick back schemes, and seem more concerned with funnelling generous payments into the pockets of their directors than with producing food.

The alarming side effect of this type of investment is the commodification of land and the marginalisation of communities that rely on it. Wherever the Siva Group and its like go, they secure title to vast parcels of land by any means necessary – often without the meaningful consent of the affected communities. They then leverage these landholdings for cash and credit to turn still more deals.

Governments have so far done little, if anything to protect their people from this new wave of predatory investment. Their efforts have focussed more on providing investors with safeguards and incentives, while proposing only voluntary guidelines to keep corporate responsibility in check. The door is thus wide open for financial players like Sivasankaran to grab lands and make quick profits, undermining food systems and the livelihoods of farmers in the process.

Playing the commodities supercycle

Sivasankaran made his fortune, estimated at US$4 billion, from mobile phone networks, broadband internet services, and sales of discounted PCs in India. But these days he’s more concerned with commodities.

He believes in a commodities supercycle, in which population and economic growth will drive increasing demand for natural resources and agricultural commodities, pushing up global prices. And he thinks Africa will be the main source of raw and processed materials to feed this growing demand. So that’s where he’s pouring most of his money – buying up shipping lines, oil and gas reserves, mines and plantations.1

When it comes to agriculture, Sivasankaran’s bought up olive farms in Argentina’s Catamarca Province and started contract gherkin production in India, but his main focus is palm oil.2 As the world’s cheapest vegetable oil, it is always in high demand to produce such things as processed foods, cosmetics and biofuels. Demand is particularly strong in Sivasankaran’s home country, India, which, in a mere decade and a half, has gone from being a marginal consumer to the world’s largest palm oil market.3

Sivasankaran began investing in oil palm plantations shortly after the food price crisis of 2007-8. He started by buying shares in several Indian vegetable oil processing companies, like Ruchi Soya and KS Oils, that were making forays into oil palm plantations. Then he set up his own oil palm company and got decidedly more involved.

Island hopping

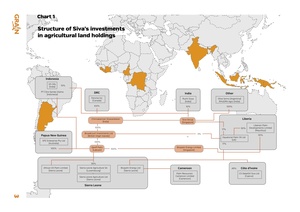

Sivasankaran’s agricultural investments are channeled through a complex web of offshore tax havens. Money flows through these two companies into yet more offshore jurisdictions and eventually into the companies set up to actually take over lands and run oil palm plantations. Figure 1 provides a detailed look at how Sivasankaran’s agricultural investments are structured.

In a number of countries, Sivasankaran has chosen to buy out or take significant stakes in existing oil palm plantation companies. This is the case in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In most of these cases, the companies he’s bought into are obscure ventures set up by people from the mining or logging industries. They have little or no background in agriculture – but they do have the political connections needed to obtain rights over large areas of land. Lacking the technical capacity or capital required to operate large-scale plantations, these companies need backers like Sivasankaran to provide financing to get them far enough along to be able to sell their operations to larger players.

In Cameroon, however, Sivasankaran’s set up his own oil palm plantation company and fully controls the process for acquiring lands and setting up operations. He’s also moving in this direction in Papua New Guinea and Indonesia, where he has full control of subsidiaries, and Sierra Leone, where he’s set up two of his own companies and acquired 95% control over another. Sivasankaran’s even said to be prospecting for oil palm in Belize, where he’s established a subsidiary.4

Building an empire

A manager with the Siva Group says that their near term objective is to have control over a total of 200,000 ha of plantable lands in each of at least four African countries and another 200,000 ha in Papua New Guinea.

Already, through his various joint ventures and holdings, Sivasankaran has signed deals covering nearly 600,000 ha, an area of land comparable to the holdings of the largest corporations in the palm oil sector. Sime Darby, the world’s largest oil palm planter, has 860,000 ha, and Wilmar, the world’s largest palm oil producer, has 331,000 ha.5

Only a small percentage of the land Sivasankaran’s companies have acquired, however, has been cleared or planted to oil palms. Most still consists of farms and forests belonging to local communities – many of whom, if they are even aware of Sivasankaran’s land deals, have no intention of letting his companies operate there. Indeed, on closer inspection, Sivasankaran’s land bank – a term commonly used by oil palm companies to refer to the lands they have acquired rights to that are both planted and not yet planted – is far from secure, as there are grave doubts about the legality of the deals. There are also questions about whether the companies he controls to actually intend to develop the lands they have claimed. Most of these companies have failed to produce very much food or even turn a profit; but they have been very useful for shifting finance and debt around and paid their directors handsome salaries.

Contested land deals and covert payouts in Liberia

Sivasankaran made his move into Liberia’s oil palm industry by buying shares of the UK company Equatorial Palm Oil (EPO) Ltd. The Siva Group began buying shares in EPO in 2010 and by 2013 it had effectively gained a controlling interest through a 36.7% stake and a 50:50 joint venture with EPO based in Mauritius, called Liberian Palm Developments Ltd, which held EPO’s Liberian land concessions.6

In April 2011, Liberian media reported that EPO Director Peter Bayliss handed President Sirleaf an envelope containing a cheque for $25,000 at a public event during a visit to the concession site. (Photo: Frontpage Africa Online)

In April 2011, Liberian media reported that EPO Director Peter Bayliss handed President Sirleaf an envelope containing a cheque for $25,000 at a public event during a visit to the concession site. (Photo: Frontpage Africa Online)

EPO acquired two major land concessions for oil palm development from Liberian companies. The first one, based around an old plantation in Butaw, was acquired by EPO when it took over Liberian Forest Products Inc. (LFPI) on August 21, 2006. At that time, EPO was a small company known as Nardina Resources PLC, set up the year before by a group of London investors from the mining industry. The company claimed that the takeover of LFPI gave it rights to 700,000 ha of land in Liberia – equal to about 6% of the country’s entire land area. Nardina then changed its name to Equatorial Biofuels PLC and then again to EPO and gave itself a new mandate as a palm oil company.

Very little is known about LFPI or how it could have acquired the rights to such a huge chunk of land at a time when the country was just emerging from a brutal civil war and was still governed by a National Transition Government.7 EPO’s disclosure documents from its listing on the London AIM stock exchange in 2010 show that it paid £1,555,000 in shares and cash for the purchase of LFPI. This payment was made to two offshore companies, Kamina Global Ltd of the British Virgin Islands and Subsea BV of Liberia, which each held a 50% share in LFPI. Documents retrieved from the business registries for these two companies do not reveal who the actual beneficial owners of the companies are.8

When EPO acquired LFPI, the contract was under examination by Liberia’s Public Procurement and Concession Commission. It would conclude that the agreement contained “gross irregularities and non-compliance with the law” and the company was forced to renegotiate. LFPI, by now owned by EPO, signed a new contract with the government in 2008, this time covering much less land than the company had originally announced but a still valuable and hotly contested 55,000 ha concession in Butaw.

The Jogbahn Clan has persuaded the Liberian government to recognise its right to reject encroachment onto their land. (Photo: Cargo Collective)

The Jogbahn Clan has persuaded the Liberian government to recognise its right to reject encroachment onto their land. (Photo: Cargo Collective)

The second concession acquired by EPO was in Grand Bassa County. That concession has a long, controversial history going back to 1966 when 14,000 ha were allocated to a Liberian company owned by the richest man in the US, J. Paul Getty, without consultation with the local people.9 Getty didn’t get very far with developing the land as a plantation before selling it in 1980 to Joseph Jaoudi, the son of one of the richest businessmen in Liberia and a close family friend of the current Liberian president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. He too struggled to develop the plantation. By the time the lease ran out in 2006, only around a third of the lands had been cleared.

But rather than give up on the lease, Jaoudi made a move to take control of even more land. In 2007, he transferred the concession to a newly established Liberian company called LIBINCO, whose owners included Jaoudi and John Bestman – the former governor of the Central Bank of Liberia, twice Liberia’s minister of finance and the leader of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s election campaign in 2005.10 LIBINCO was able to renew the lease with the Government of Liberia and renegotiate the terms, giving LIBINCO an additional 20,000 ha of lands – once again without any consultation with the affected population. In return, the company promised to develop an outgrower scheme on half of the new lands and to invest over US$5 million within the next 4 years.11

Yet less than a year later, in February 2008, LIBINCO turned around and sold the concession to EPO, with Jaoudi, Bestman and their unknown business partners collecting £3,134,000 in cash and EPO shares.12

Jaoudi, Bestman and the unknown owners of Kamina Global and Subsea BV pocketed millions of dollars for simply flipping land permits over to EPO. And the founders and directors of EPO made a bundle too. While EPO has suffered multi-million dollar losses in every year of operation and has only managed to bring a small fraction of its land concessions into operation, its directors have been rewarded with large salaries. In 2010, with EPO recording losses of US$4.4 million and still not pulling in any revenues, the top three executives of the company, based in the UK, were paid a combined US$513,000, which does not include additional share-based compensation.

Sivasankaran does not appear to have fared so well. In 2013, after pouring at least US$50 million into the company, the Siva Group cashed out of EPO, selling all of its interests in EPO’s Liberian operations to the Malaysian palm oil giant KL Kepong (KLK) at what was likely a loss of several million dollars. But perhaps his investment in EPO was about more than share prices? In 2011, Sivasankaran’s Mauritius joint venture with EPO provided his Malaysian subsidiary with a US$10 million loan that he used to finance the acquisition of a 110,000 ha oil palm concession in Papua New Guinea.13

The other bright side for Sivasankaran is that the sale to KLK kept him out of what is turning into an increasingly ugly conflict over EPO’s land concessions. The situation is especially tense at the Palm Bay Estate, where EPO has been trying to expand its plantations. The Jogbahn Clan, which lives on these lands, says it was never consulted over the creation of the 34,500 hectare concession. Their objections to the clearing of new areas and a land survey begun in 2013 were answered by the deployment of a paramilitary police unit.

But they continued to resist, and in early 2014, the Liberian president promised the company would not be allowed to expand on the community’s lands. EPO continues to conduct studies of the Clan’s land in preparation to clear it for planting.14

Guns for hire in Sierra Leone

One of the early investors in EPO’s Liberian operations was the gold prospector Daniel Betts. He is heir to a UK precious metals company and owner of another 700,000 ha land concession in Liberia, in this case for gold mining.15

Betts was active in neighbouring Sierra Leone too. In 2008, he and a few other London based investors established the Aristeus Palm Oil company and soon succeeded in getting a major investment from Angad Paul, son of business magnate and UK Labour Party insider Sir Lord Paul. The name of the company was then changed to Sierra Leone Agriculture (SLA) and it was newly registered in the tax haven of Luxembourg.16 Paul became a director, as did Tim Collins, a celebrated former lieutenant colonel in charge of the UK’s Special Forces in Sierra Leone in 2000 and Iraq in 2003.17

SLA hired Kevin Godlington, another UK army veteran with experience in Sierra Leone, as CEO and immediately sent him to the country to find lands. Godlington’s first deal was a 2010 lease with the Paramount Chief of Bureh Kasseh Maconteh Chiefdom in Port Loko District, giving SLA’s Liberian subsidiary, Sierra Leone Agriculture Limited, 42,000 ha of land for oil palm plantations.18

Over the next few years, Godlington signed a series of lease agreements with various communities in Sierra Leone on behalf of different companies.

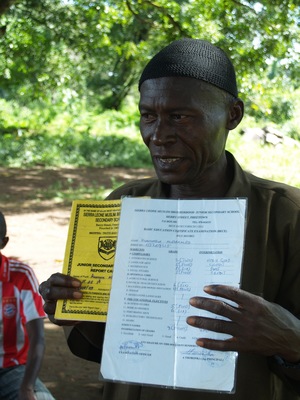

Sallay Koroma was forced to take two of his three children out of school after he lost his land to the Sierra Leone Agriculture company, now owned by Siva. (Photo: Joan Baxter)

Sallay Koroma was forced to take two of his three children out of school after he lost his land to the Sierra Leone Agriculture company, now owned by Siva. (Photo: Joan Baxter)

Subsequent interviews conducted by researchers with community members whose lands had been leased out under the deals with Godlington reveal that most community members were unaware of the details of the contracts. They were often pressured into accepting the agreements by the paramount chiefs or by promises of benefits not provided for under the lease agreements. At one meeting where an SLA lease was signed, community members say that women and youth were not allowed to speak and that they only agreed to provide the company with a small portion of the lands it later claimed. According to those interviewed, only the paramount chief, the member of parliament and “the white people” knew that the agreement involved all of their land.19

Every company that Godlington arranged leases for is registered to the same address in Freetown.20 That address belongs to the law offices of B&J Partners, which is run by Chernor Bah and Alpha Jalloh, two of the most powerful young men in Sierra Leone, with tight connections to the country’s president, Ernest Koroma. Bah, also known as Chericoco, is Deputy Speaker of Parliament and Chairman of the Parliament’s Mines and Minerals Committee, where he has been a ferocious advocate for foreign mining companies.21 Company documents indicate that he owns 1% of Sierra Leone Agriculture Ltd.22

In 2010, the Siva Group bought up SLA and its questionable land leases from Paul, Collins, Betts, Bah and the other shareholders. Inside sources say Siva paid US$5 million in a package deal that also included African Oil Palm Limited, a company with a 39,000 ha lease in Pujehun.

The affected communities only found out about the sale after the fact. “That makes us so sad, angry and disgusted,” said one community member from the area of the SLA land lease.23

SLA is not Sivasankaran’s only pathway to acquiring lands in Sierra Leone. At around the same time that he bought SLA, he set up a subsidiary and hired Dutch businessman Willem Tijssen to identify and acquire lands in the country.

“Willem basically knew Sierra Leone better than us,” says Gagan Pattanayak, Senior Manager of the Siva Group. “He had some connection with the chiefs and local people so his idea was to go to different chiefdoms, so the first round was actually done by Willem and me, and I had visual inspections of land and I took parcels and we sat with the people. Willem’s role was to ensure we get the land.”24

So far, Tijssen’s helped Siva Group, through its subsidiary Biopalm Energy, acquire two leases covering nearly 60,000 ha in Pujehun District and is helping them to negotiate for another three in Bo and Kanema Districts.

Tijssen is a controversial figure who is close to Liberian political insider John Bestman, who was involved in the LIBINCO deal with EPO in Liberia. Together Tijssen and Bestman own the Liberian company Mano Properties & Investment Inc, which claims to have rights to 400,000 ha in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea.25

A 2012 undercover documentary by Danish filmmaker Mads Brügger exposed Willem Tijssen and John Bestman for their roles in helping European businessmen secure backdoor access to Liberian politicians for payment.26 In this case, they arranged for Brügger, posing as a diamond trafficker, to be appointed as Liberia’s Honorary Consul to the Central African Republic so that he could more easily smuggle diamonds out of the country.27

Côte d’Ivoire: the land deal that never was

One of the reasons why Sivasankaran decided to invest in oil palm plantations in Côte d’Ivoire was because of access to lands. Siva Group’s Senior Manager Gagan Pattanayak says the process for acquiring lands in Côte d’Ivoire is better than in other African countries.

“If you go to Liberia, the Liberian government issues you a concession, the local people don’t agree, the president of the country tells them that the government agrees so you must agree. If you go to Cameroon, again it is basically the government that gives you the land,” says Pattanayak. “It’s much better in the Ivory Coast. They have a whole system in fact, because Ivory Coast you don’t get land which is lying idle; mostly land has been put to collective use. I think there is a proper title system there.”28

Pattanayak is partly right. There is very little farmland lying idle in Côte d’Ivoire and, yes, there is a system of individual land titles. But the land titling system is highly dysfunctional and land ownership in Côte d’Ivoire is as complicated and politically sensitive as anywhere else in Africa. In much of the country, there are tensions between families considered indigenous to the area, and others that have migrated in from elsewhere. The migrants rent, or have been allocated, land which they have cultivated for many years – in some cases for several generations. In this context, when land conflicts erupt they can be explosive, as witnessed in the post-election violence of 2010-2011. The recent interest in the country’s agricultural lands from foreign corporations, which has been encouraged by the government, has only exacerbated conflicts over ownership and access.

Sivasankaran’s entry point into this fragile context has been through a partnership with DekelOil, a Cyprus based palm oil company founded by Israeli businessman Youval Rasin and his family’s Israeli conglomerate, the Rina Group. In 2008, Siva Group and DekelOil formed a Cyprus registered joint venture company called CS DekelOIl Siva Ltd, 49% owned by Siva Group and 51% owned by DekelOil, which controls all of the land holdings for the two companies in Côte d’Ivoire.

Siva claims to have so far acquired a 1,886 ha oil palm plantation and to have signed three separate agreements with cooperatives, small farmers and local landowners that will give the company lease rights to another 27,000 ha around Ayenouan and 24,000 ha in Guitry once fully implemented.29

The land deals in Côte d’Ivoire are different from Sivasankaran’s concessions elsewhere. Under its agreements with cooperatives in Ayenouan, DekelOil supports the participating cooperative members in getting individual land titles, and they then lease their lands to DekelOil and provide the company with exclusive rights to the palm oil production. In exchange, DekelOil agrees to pay them a percentage of the net profits derived from the palm oil that it produces on their land.

A similar situation could unfold in the Guitry region where CS DekelOil says it will soon be expanding. The company claims it has already secured rights to over 24,000 hectares of land suitable for palm oil development in the area. Lincoln Moore, the Executive Director of DekelOil, says these rights are based on an April 2011 agreement with a local company called Ivoire Agro Developpement (IVAD).30 DekelOil maintains that IVAD signed an agreement earlier in 2011 with the two families that own these lands, under which “IVAD was to find an investor to develop the land in consideration for 2,000 ha of land” and was granted “the right to offer use of the land to third parties”. IVAD and DekelOil then signed deals giving DekelOil a 50-year lease to the lands, including IVAD’s 2,000 ha, in exchange for a series of payments to IVAD totalling 1.5 million euros.31

The owners of IVAD are not the only ones sucking up millions from DekelOil’s accounts. The company’s directors, managers and numerous consultants, public relations managers and financial advisors guzzle up the vast majority of its annual expenditures. In 2010, the company’s administrative expenses outweighed its operating expenses by a stunning factor of nearly 10:1 – 2.3 million euros versus 242,000 euros.32

Youval Rasin, DekelOil’s CEO and largest shareholder, is entitled to a 50,000 euro bonus and an annual salary of 240,000 euros now that the first mill is in operation. Companies he controls through his Rina Group are also paid over 150,000 euros per year by DekelOil for office space in Abidjan and Israel, while another Rina Group subsidiary, Starten Ltd, gets regular payments from DekelOIl that are not clearly accounted for in the company’s financial statements: 50,000 euros in 2010, 141,000 euros in 2011 and 80,000 euros in 2012.

With all the cash being drained from the company by its directors and foreign consultants, it’s hard to imagine that DekelOil will ever achieve profits within Côte d’Ivoire. If it were to, those profits won’t be taxed. In March 2014, the Government of the Côte d’Ivoire granted the company a 13 year tax exemption on profits from its palm oil mill.33

Rights to the Guitry lands were central to DekelOil’s fundraising on the AIM stock exchange, and have since been highlighted in company communications as a basis for the expansion of its operations.34

But when GRAIN spoke to local authorities in Guitry and representatives of the two land holding families, they fiercely denied having given rights to their lands to DekelOil. They said that discussions with DekelOil had taken place but that they had rejected the company’s offer. Moreover, the family members said that no one in their families had ever negotiated a contract with IVAD.

“No official document of any kind was ever signed that could give DekelOil rights over our lands,” said Mr. Titikpeu, from the village of Tiegba, where DekelOil claims to have rights to land. “Our family refuses any claims that DekelOil or IVAD make to having rights over our lands.”

GRAIN was unable to confirm this with IVAD, since there is no contact information available for the company and there are no offices at the address where the company is registered.

A looming conflict with the Bagyeli people in Cameroon

Sivasankaran operates in Cameroon through a local subsidiary, Palm Resources Cameroon Limited, that is owned by Biopalm Energy Ltd.In 2011, the Siva Group signed an MOU with the Government of Cameroon in which the government agreed to provide it with 200,000 ha for oil palm plantations in the Ocean Department. Biopalm says the Government then identified two initial parcels of 3,348 ha and 21,552 ha in the Lokoundje subdivision for the company to develop. Biopalm was issued a provisional 3-year lease by Presidential decree on 28 March 2012 for the smaller parcel and the company says it is still in the process of demarcating the lands for the second parcel.35 But the land is within the territories of the indigenous Bagyeli people, who maintain they did not provide their consent and who have issued a collective petition against the project.36

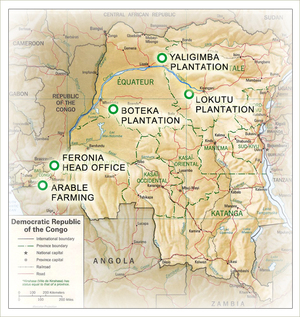

Kleptomania in the Congo

Another company that Sivasankaran has sunk money into, Feronia Inc, epitomises the new era of agricultural investing in Africa that erupted with the food price crisis of 2008. Led by a financial “whiz kid” from Toronto, Canada’s Feronia aimed to revitalise African agriculture by marrying the money of today’s sophisticated financial markets with the crumbling agricultural projects of a bygone colonial era.

“Feronia has the potential to reproduce the agricultural revolution that has occurred in Brazil over the past 30 years,” claimed its CEO Ravi Sood, after the company made its first investment in African farmland in 2009.

Sivasankaran was one of those who bought into the magic of Feronia. In 2010, he made a crucial investment in the company, spending millions to take an 8.6% stake. Soon after, Feronia went public on the Toronto Stock Exchange.37

But Feronia’s sparkle didn’t last long. By 2014, its stocks were nearly worthless, Sivasankaran had quietly exited the company, and European development finance institutions had stepped in to pick up the pieces in what effectively amounted to a bailout. What went wrong?

Sood was a darling of Toronto’s financial district and a rising star of the prestigious investment house, Lawrence & Co. He was especially known for his international connections in the resource sector. By the age of 32, he was at the helm of one of Lawrence & Co’s main subsidiaries, Lawrence Asset Management (LAM), and responsible for several LAM managed funds focussed on emerging markets. Sood used one of these funds, TriNorth Capital, to bankroll Buchanan Renewable Energies Inc, a company he and another LAM partner, Joel Strickland, founded in 2006 to export wood chips from the rubber trees of abandoned Liberian plantations to Europe for biomass energy production.

Two years into operations, however, and the company was in trouble. Logs were reported to be stacked up and rotting at Liberia’s Buchanan Port, and losses were pilling up even faster – hitting $5.8 million for 2007. Only a bridge loan of $5 million and a generous takeover bid by a Canadian billionaire philanthropist and friend of the Liberian President saved Buchanan from collapse and allowed TriNorth to exit without losses.38

After cashing out of Buchanan in May 2008, Sood enlisted the help of James Siggs, who had also helped set up Buchanan, and went hunting for another African investment for Sood’s LAM managed funds, this time with a focus on agriculture. Siggs, a UK consultant on large-scale overseas agriculture projects who had worked for Unilever, engineered a deal to take over Unilever’s oil palm plantations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).39

The deal was done by way of a Cayman Islands company called Feronia Inc, that Sood created in 2008 and pumped up with over US$6 million in cash taken from LAM managed funds under his control.40

In September 2009, Feronia Inc acquired 76% of Plantations et Huileries du Congo SARL (PHC) for US$3,854,551 from a Unilever holding company.41 The Government of the DRC retained its 24% stake in the company.

Sood then went fundraising to finance Feronia’s operations through a $20 million private placement, linked to the company’s successful listing on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Sivasankaran was one of the main investors in this round of financing.

Perhaps Sivasankaran did not fully understand what he was walking into. His investment predates Feronia’s listing on the Toronto Stock Exchange, which requires companies to reveal detailed information about their operations. There are some serious red flags within these records that any major investor should have known about.

The most glaring reason for concern is the involvement of Barnabe Kikaya bin Karubi, the DRC’s Ambassador to the UK since August 2008 and former Private Secretary to President Joseph Kabila. He is known to still have close, direct communications with the president.42

Kikaya sits on Feronia’s Board of Directors. For his services as Director, Kikaya gets a relatively small annual fee of US$10,000-20,000 per year. But he also collects between US$120,000-150,000 every year in rental fees from Feronia for his lease of a “house and apartment in Kinshasa”.43 That property happens to be located at the same address as Kikaya’s family residence.44

When Feronia purchased PHC from Unilever, the deal was structured through a Cayman Islands’ subsidiary of Feronia Inc, called Feronia JCA Ltd. This subsidiary was, for unspecified reasons, 20% owned by Kikaya.45 Shortly after acquiring PHC, Feronia Inc acquired Kikaya’s share of Feronia JCA in exchange for the issuing of 8,894,344 shares in Feronia Inc, valued by the company at over US$2.2 million. The deal included the acquisition of a farm from Kikaya, which Feronia says had a value of over US$600,000.46 This farm asset, however, does not appear on Feronia’s books after its mention in its financial statements of September 2010.

All told, Kikaya’s on record as having received at least US$3 million in cash and shares from Feronia since 2009.

Another red flag appears in the company’s initial prospectus, released as part of its listing with the Toronto Stock Exchange. In the weeks after it purchased PHC from Unilever, Feronia says it became aware of certain issues that caused it to adjust the value of the company downwards by staggering US$10,569,288. Feronia only bought PHC for US$3,854,551. Meaning, if the assets had been valued correctly, Unilever should have paid Feronia $6.7 million to take the company off its hands.

There were two main issues that Feronia had not noticed. One was that a key palm oil mill was dysfunctional. The other was an employee incentive liability scheme worth US$8,977,030 that Feronia says was not on Unilever’s books.47

One wonders how Feronia’s management could not have known about these two critical pieces of information, especially given the continued involvement of the DRC government and the experience that certain Feronia managers had in working with Unilever. If Unilever had hidden the information, clearly there would be grounds for litigation, but Feronia never pursued this option. The huge loss was simply placed on the books, and the losses have accumulated ever since.

Investors in TriNorth and other Sood managed funds spent millions of dollars buying a less than worthless plantation company in the Congo.48 By the end of 2009, TriNorth had lost 90% of its value. Sood’s November 26, 2009 letter to the shareholders of TriNorth made no mention of the huge hit they had taken from the devaluation of Feronia’s assets.49

If the funds that Sood has managed have suffered badly from their involvement in Feronia, Sood himself and the other Feronia managers and directors have done quite well. Sood collects large fees for the funds he manages that invest in Feronia.50 He is also awarded fees and share options for his position as Executive Chairman of the company. For instance, in 2011, Feronia paid Sood $150,000 in cash and $101,000 in share-based awards. Plus, a company owned by his wife was paid US$131,000 that same year for “corporate development services”. In 2010, her company was paid $256,754 for supply of services and expenses.

James Siggs, Feronia’s CEO until 2011 and the person who led Feronia’s disastrous take-over of PHC, has also been generously rewarded.51 In 2010 alone, Siggs was paid US$616,000 in fees and share options. When he was replaced as CEO the following year, he received a compensation package of US$317,379. Even Feronia’s accountant, Georgina Cotton of the UK, got a hefty US$306,000 in total compensation in 2010. That year the top 4 managers raked in around US$1.5 million in fees, while the company clocked US$6.5 million in losses, which was in fact an improvement on the US$11 million it lost in 2009.

Part of Feronia’s annual multi-million dollar losses are absorbed by the DRC Government, which continues to own nearly a quarter of the company’s plantation operations. The DRC Government also loses when it comes to tax revenue.

Just before Feronia took over PHC, Unilever sold off a number of villas and other properties that were owned by the company. These helped pay off some of the company’s debts and put PHC in the black. In 2008 and 2009, PHC made profits of US$2,935,932 and US$5,525,518. For those years, it should have paid the DRC government over US$3 million in taxes. But Feronia refused to pay the tax bill, claiming that it qualified for a tax holiday offered by the DRC government to foreign investors. The taxes were dropped and neither Feronia nor Unilever paid taxes on those profits.

Congolese workers on Feronia’s plantations don’t benefit from this generosity. In interviews with Feronia workers, the Réseau d’information et d’appui aux ONG nationales (RIAO-RDC) documented wages ranging from $2.22 per day for a middle aged man working at the Feronia tree nursery, to $2.00 per day for a man harvesting bunches, to just $1.25 per day for a woman in her fifties working at the plantation. The payslips they examined showed even lower daily wages of $1.39 and $1.17. According to the chair of RIAO-RDC, Jean-François Mombia, the company will not pay workers these already abysmal daily wages if they do not complete the difficult tasks demanded of them. For instance, a worker harvesting bunches must collect 60 large bunches or 100 small bunches per day. If she or he fails to meet this target, the company withholds their wages or pays them only half of what they’re due.

The only thing that has kept Feronia above water is the surprising interest of investors. Initially, those investors were people, most if not all of them Canadians, who had entrusted Ravi Sood with their savings. Through constant dilution in shares and a plunging overall share price, they lost pretty much everything. Sivasankaran could well have lost a bundle too, but in late 2012 and 2013, a new investor came in to salvage Feronia: governments.

The UK’s Commonwealth Development Corporation and the African Agriculture Fund, which is managed by the private equity fund Phatisa but backed by multilateral banks and French and Spanish development finance agencies, bought $35M worth of Feronia shares. Together they now own 60% of the company. They are the ones who now have to bear the brunt of Feronia’s ongoing losses, which came in at US$10.1 million for the 2013 financial year. They also now bear the risks owing to the implementation of a new law in the DRC called the “loi portant principes fondamentaux relatifs à l’agriculture” that came into effect on June 24, 2012. Article 16 of that law stipulates that land can only be attributed to companies that are majority owned by national investors. Feronia says that it “has been and continues to be involved in discussions with various levels of government in the DRC regarding the interpretation of the law” but it remains quite possible that Feronia could be forced to relinquish much of its ownership in PHC and its arable farming division, which has another 10,000 ha.52

Sivasankaran in the heart of oil palm country – Indonesia

Sivasankaran’s Labuan company, Geoff Palm Ltd, has also made its own, direct purchase of an oil palm plantation in Indonesia. It recently acquired the Indonesian company PT Citra Ganda Utama, giving it ownership of a 3,000 ha plantation in East Aceh.

Preying on Papua

In May 2011, Sivasankaran made his first foray into Papua New Guinea (PNG) – viewed by the industry as a new frontier for oil palm expansion. His subsidiary, Geoff Palm Ltd, which is based in the offshore tax haven of Labuan, Malaysia, acquired the Australian company SPZ Enterprises Pty Ltd (SPZ). SPZ has a sub-lease for a 110,000 ha concession in Nungwaia, East Sepik Province, covering an area known as the Nungwaia Bongos Integrated Large Scale Agriculture Project.

Sivasankaran financed the deal in part through a $US10 million loan from his 50:50 Mauritius-based joint venture with EPO, Liberian Palm Developments.53

These lands were a forest management area belonging to around 230 local clans or “Integrated land groups”, before they were converted to a Special Agriculture and Business Lease and granted in April 2011 to a company called the Nungwaia-Bongos Rainforest Alliance that is owned by local member of parliament Tonay Aimo and a few other influential local people. As soon as it had acquired the lease, Aimo’s company granted a 99 year sub-lease to SPZ Enterprise Limited, an Australian company owned by Australian Chinese businessmen Peter Song and Jijun Zhang, neither of whom have any prior experience in agriculture. A month later, SPZ was taken over by Sivasankaran’s Geoff Palm for an unknown sum.

The people of Nungwaia are furious about this flurry of deal making. They say that they were not properly consulted and that consent was only given by a few people who do not represent the whole community. Most have not even seen the relevant documents and do not know who signed them on their behalf. And yet, in its communications with the community, Geoff Palm representatives have told them that if they stand in the way of the project, the community will have to reimburse the company for the millions of dollars that it has already invested.54

Passing the buck

The argument for foreign investment in agriculture is that it brings in much needed money. But the investments made by Sivasankaran indicate that such foreign investment does a much better job of taking money out. The money that flows in (if it ever arrives), quickly flows back out into the pockets of the foreigners that run the company or into the offshore bank accounts of the local elites paid off as part of the operation. At times, the primary concern seems to be to secure so-called land banks, that companies can use to raise more funds or access loans to finance other projects.

True, some of the money does go into hard, on-site investments and jobs. But there are much more efficient methods to generate this investment, in ways that keep control and profits in the hands of local farmers, as in the peasant-owned and controlled palm oil cooperatives in Honduras.55

Peasant palm oil cooperatives were created in Honduras as part of an agrarian reform project in the 1960s and 70s, which granted land, infrastructure, credit and extension services to peasants in the Aguán Valley –a region previously dominated by foreign-owned banana companies. Hondupalma, the country’s leading palm oil cooperative, was formed by several thousand families that migrated to the Aguán Valley.

Over the past couple of decades, the cooperative has invested US$25 million of its own revenues in state-of-the-art mills and other equipment. Feronia’s PHC has been around for far longer, has spent far more money and has a 100,000 ha land bank at its disposal, but it produces only 8,300 tonnes of crude palm oil per year and its workers live in slave-like conditions. Feronia’s PHC has been around for far longer, has spent far more money and has a 100,000 ha land bank at its disposal, but it produces only 8,300 tonnes of crude palm oil per year. Unlike Feronia, Hondupalma keeps all of its profits within the country and it provides its members and the communities in which it operates with real services, such as a cooperative bank, low-cost medical centres, and free education centres.56

The traditional oil palm production and processing systems of West and Central Africa are even more impressive when it comes to the economic and social benefits they provide to local people, especially the women who carry out most of the production, processing and marketing. West and Central African peasants cultivate their oil palms in mixed farming systems with a number of other crops or harvest them from semi-wild groves in forested areas that they have protected and cared for for generations. Production costs are near zero, but the contribution each oil palm makes to local food systems and people’s livelihoods is immense. From the nuts to the fronds, every part of the oil palm is used for dozens of different purposes, from foods to medicines to textiles.57

Traditional palm oil producers in Liberia: a new wave of investment threatens to push peasant farmers like these members of the Jogbahn Clan off their land and erode food sovereignty. (Photo: Cargo Collective)

Traditional palm oil producers in Liberia: a new wave of investment threatens to push peasant farmers like these members of the Jogbahn Clan off their land and erode food sovereignty. (Photo: Cargo Collective)

Nor can it be claimed that foreign investment in agriculture is entirely a private affair. Like many other private sector-led projects, Sivasankaran’s investments are often backed up by public agencies, such as DekelOil’s financing from the Banque Ouest Africaine de Développment or the investments made by several European development finance institutes in Feronia’s shares. Moreover, all Sivasankaran’s investments have benefited from generous tax holidays given by local governments and from lax corporate regulations in offshore tax havens that ensure that hardly any revenues generated go into government coffers.

But perhaps the most serious problem with foreign investment in agriculture is that it advances a process of land commodification. To get access to foreign capital, companies like EPO or Sierra Leone Agriculture need to acquire lands. So they use whatever means they can to sign land deals, often without meaningful consent from the affected communities. The land leases or purchases then become commodities that can be traded and speculated upon by global finance; or crafted by sophisticated money managers into wells of credit and cash that extend well beyond their actual value.

The communities living on the lands are an afterthought, a potential obstacle to the money making. But they are the ones who ultimately pay the price.

Some of the characters involved in Sivasankaran’s agriculture investments

Kevin Godlington

A UK Special Forces veteran, Godlington first became involved in the oil palm sector in 2008 when he became CEO of Angad Paul’s company Caparo Renewable Agriculture Developments Ltd and director of Sierra Leone Agriculture Ltd (UK). He then became CEO of Sierra Leone Agriculture S.A. when it was established in Luxembourg in 2009, with funding from Paul. Godlington is listed as a director and shareholder of several companies that have acquired leases for oil palm in Sierra Leone, including Sierra Leone Agriculture, African Oil Palm Limited, Aristeus Palm Oil Ltd, Aristeus Agriculture Limited, West African Agriculture Ltd and West African Agriculture Number 2 Ltd. But he says his main interest in Sierra Leone is his orphanage, Network for Children in Need.

(Sierra Leone)

Angad Paul

Paul is the son of Indian-British industrialist Lord Swraj Paul and CEO of the family’s steel company, the Caparo Group. In 2009,Caparo acquired a controlling interest in Namibia Agriculture and Renewables and Sierra Leone Agriculture through its subsidiary CRAD-L. Paul and the other shareholders and directors of Sierra Leone Agriculture, with the exception of Kevin Godlington, sold their stakes to Siva Group in 2011, after having acquired a 42,000 ha land lease in Porto Loko Distict. Gramercy, a private equity company with Paul as Chairman, claims to still own a 1000 ha pineapple plantation in Yoni District, Sierra Leone – the same district where Kevin Godlington claims to be involved in a pineapple plantation.

(Sierra Leone)

Tim Collins

Collins is a former UK Army Colonel who commanded the UK’s Special Forces operations in Sierra Leone in 2000. Nicknamed “Nails” by his soldiers, Collins is best known for the eve-of-battle speech he gave in Kuwait in 2003. Collins became a director of Sierra Leone Agriculture when it was acquired by Angad Paul in 2009 and relocated to Luxembourg. At the time he was also Managing Director of the private investigation company RISC Management, which would later be shown to have been at the centre of a major bribery case during the same period, involving Scotland Yard inspectors and the corrupt former Governor of Nigeria’s Delta State James Ibori. Collins left Sierra Leone Agriculture in 2011 when it was acquired by Siva, and today is the CEO and co-founder of the military intelligence company New Century Consulting.

(Sierra Leone)

Chernor R.M. Bah

Lawyer Chernor “Chericoco” Bah is a Member of Parliament of Sierra Leone, where he is Deputy Speaker, Chairman of the Public Accounts Committee and Chairman of the Mines and Minerals Committee. He is also deeply involved in a powerful, secretive political organisation called “All Works of Life Development Association” (AWOL) that is tightly connected to President Koroma and bankrolled by the country’s richest man Moseray Fadika, aka Super, who is rumoured to be a successor candidate to Koroma. Bah operates out of the law offices of B&J Partners, with AWOL’s Vice Chairman Alpha Jalloh, eldest son of the Minister of Mineral Resources, and Ady Macauley, a prosecutor with the Anti-Corruption Commission and a shareholder in at least two Kevin Godlington-linked companies. All of the companies linked to Godlington that have acquired large agricultural land leases in Sierra Leone are registered or connected to the address of B&J Partners, including Sierre Leone Agriculture, which was 1% owned by Chernor Bah until it was acquired by Sivasankaran in 2011.

(Sierra Leone)

Willem Tijssen

A businessmen and political insider, Tijssen has set up several companies active in Africa, including the West African Landbank and Star Model Africa. He describes himself as a consultant to the Guinea Government, special consultant to the Government of Liberia and special envoy for the Mali Presidency in Europe. He and John Bestman own Mano Properties & Investment Inc, which claims to have rights to 400,000 ha in Libera, Sierra Leone and Guinea that can be developed into oil palm plantations. Tijssen was hired by the President of Guinea in 2006 to find investors to exploit Mount Nimba iron ore resources, offshore oil deposits, and onshore natural gas deposits. A 2012 documentary by Danish filmmaker Mads Brügger exposed Willem Tijssen and John Bestman for their roles in helping European businessmen secure backdoor political connections to Liberian politicians for payment. The Siva Group hired Tijssen to use his political connections to help them identify and secure leases for oil palm plantations in Sierra Leone.

(Sierra Leone, Liberia)

Brima Babo

Babo is the General Secretary of the Sierra Leone National Farmers’ Union. He was hired by the Siva Group to work with Tijssen in acquiring lands in Sierra Leone.

(Sierra Leone)

Daniel Betts

Betts is heir to to the fourth-generation, family-owned, UK precious metals company, Betts Metals. In post war Liberia, Betts used family connections with Liberia’s Minister for Lands and Mines to gain permits to 700,000 ha in the eastern part of the country, where he now owns a gold exploration project. He was an early investor in Equatorial Palm Oil and founded Sierra Leone Agriculture which, after acquiring a 42,000 ha land lease in Porto Loko Distict, was sold to the Siva Group in 2010. In July 2011, Betts’ gold mining company, Hummingbird Resources, founded the Pygmy Hippo Foundation, “to promote the conservation, preservation and protection of endangered species such as the pygmy hippo in their natural environment” in Liberia.

(Sierre Leone, Liberia)

Lincoln Fraser

Fraser is described by Offshore Alert as a “British conman who masterminded the $400 million Imperial Consolidated (IC) fraud” which robbed thousands of pensioners and others of their savings when it went bankrupt in 2002. The Spanish and Israeli secret services suspected that IC was working with global arms dealer Monzer Al Kassar to run guns to Osama Bin Laden through an Argentinian gold mining company set up by a close friend of President Carlos Menem and highly overvalued on IC’s books. Bankruptcy did not prevent Fraser from subsequently establishing “a complex, multi-jurisdictional web of companies plastered with red flags.” A number of these Fraser controlled companies operate under his G4 Group – “a multi-national biotechnology, bioenergy and agricultural development and solution provider”. Its Liberian subsidiary, G4 WAO Inc. exports rubber tree logs and holds a phosphate exploration concession covering 36,000 ha in Bopolu. The company claims that “it manages in excess of one million acres of the best crop growing conditions in the world” and to have partnered with the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid-Tropics (ICRISAT) “to establish trial sites on various G4 farming enterprises in Liberia, Ghana and Kenya.” Subsea BV, which acquired a 50% stake in Liberian Forest Products Inc and rights to a land concession in Butaw that were sold to EPO in 2008, is listed as a Director of the G4 Group in the UK.

(Liberia)

John Bestman

Bestman was the former Governor of the Central Bank of Liberia, twice Liberia’s Minister of Finance and the leader of President Sirleaf’s election campaign in 2005. Bestman is said to have served as the point man in Rotterdam for war criminal Charles Taylor’s rebel forces, with responsibility for buying and sending supplies to the rebel leader as the war progressed. While he was orchestrating Sirleaf’s campaign, Bestman also entered into the shareholding of LIBINCO, a company formed to acquire and renew a lease for a large oil palm concession in Palm Bay Liberia. Soon after, the company was sold to EPO for over £3 million, with Bestman acquiring at least 400,000 shares in EPO as a result. The land concession was later transferred to a joint venture between the Siva Group and EPO. John Bestman and Willem Tijssen own Mano Properties & Investment Inc, which claims to have rights to 400,000 ha in Libera, Sierra Leone and Guinea that can be developed into oil palm plantations.

(Liberia)

Michael Frayne

Frayne is an Australian geologist who founded and directed several mining companies before co-founding Nardina Resources PLC in 2005, which later became Equatorial Palm Oil. One of Frayne’s mining companies, Asia Energy, which he co-founded with UK businessman David Lenigas, was accused by a Bangladesh parliamentary committee of doing business on the London Stock Exchange while falsely claiming to have secured resource rights to Bangladesh’s Phulbari coalfields.

(Liberia)

Lincoln Moore

Moore’s main activity is raising funds for mining exploration companies, but he became involved in investments in palm oil in West Africa around 2008. He claims to have raised US$50 million for oil palm projects in Africa through the company Ragnar Capital, which he co-founded with another mining industry player, Charlie Woods. Moore and Woods were issued 200,000 shares each in EPO prior to its 2010 AIM listing. Moore was also the Chief Financial Officer at Sierra Leone Agriculture until it was taken over by Sivasankaran in 2011. Through Ragnar, Moore claims to have arranged the €8.3 million deal which saw the Siva Group take a 49% stake in DekelOil’s Cyprius subsidiary and Moore appointed as Director of the company.

(Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire)

Richard Kouassi Amon

Richard Amon says he is a member of the Royal family of Abengorou and a relative of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the first president of Côte d’ivoire. He acts as the local partner for Israeli businessman Youval Rasin. Together they co-founded Star Energy SA, Starten and DekelOil, which is now 49% owned by Siva. Amon handles government relations for DekelOil.

(Côte d’Ivoire)

Barnabé Kikaya-bin-Karubi

Barnabé Kikaya is the Ambassador to the UK for the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and a Director of Feronia Inc. He was Private Secretary to President Joseph Kabila from 2003-6 and a co-founder of Kabila’s PPRD political party. He was elected as a Member of Parliament in 2006, but the Supreme Court ruled his election invalid a year later, at which point he was made ambassador to the UK. Kikaya-bin-Karubi has received millions of dollars from Feronia through director’s fees, lease payments for the use of his Kinshasa residence, and a US$2 million payout for his mysterious 20% ownership of a Feronia subsidiary registered in the Cayman Islands. In a 2009 cable released on Wikileaks, the US Ambassador to the UK, William J. Garvelink, has this to say about Kikaya-bin-Karubi as: “Fluent in English and comfortable around Americans, Karubi treated us to a level of candor unusual among Congolese officials, which in and of itself helped to demonstrate his own power and influence. He clearly views himself as particularly close to the president … His remarks about the ineffectiveness of non-violence … and matter-of-fact dismissal of transparency vis a vis Parliament, likewise provide an enlightening, if disconcerting, glimpse into what are probably common views about the nature of politics among the political elite in Kinshasa, although most would never dare to speak so bluntly about these issues to us.”

(Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Ravi Sood

Before the financial crisis of 2008, Sood had earned a reputation in Toronto’s financial circles as a brilliant young investor with the prestigious Lawrence & Co investment house. Lawrence & Co placed him at the helm of several funds managed by its subsidiary Lawrence Asset Management. Sood channeled these funds into several agribusiness and mining companies, including a farming operation in Saskatchewan, Canada that went bust and the loss making Congolese plantation company Feronia Inc, of which he was Executive Director. While Lawrence Asset Management collected big management fees and Sood tapped directly into Feronia for salaries and options, the funds he managed suffered badly. By 2010, his TriNorth Capital fund, which was deeply involved in bankrolling Feronia, had lost 90% of its value.

(Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Peter Song

Little is known of Chinese-Australian businessman Peter Song, other than that he and another Chinese-Australian businessman Jijun Zhang were the main shareholders of the Australian company SPZ Enterprises, whose only activity appears to have been the acquisition of a 110,000 ha oil palm concession in Papua New Guinea in 2009. Shortly after, Song sold the company and the concession to the Siva Group.

(Papua New Guinea)