The high cost of land, racial inequity and land grabbing that underpins agriculture in the United States is part of a global trend of expropriative land practice, founded upon centuries of corporate greed and colonial violence. Agrarian Trust is an active member of a global movement that seeks to heal from these destructive forces, while charting a new path forward—beginning with Indigenous knowledge, local control of the land and agroecological growing practices. Since its founding in 2010, the United States Food Sovereignty Alliance (USFSA) has worked “to end poverty, rebuild local food economies, and assert democratic control over the food system” as a partner organization of the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty. For the past two years, two organizations affiliated with Agrarian Trust, the Somali Bantu Community Association of Maine (SBCA) and the Eastern Woodlands Rematriation Collective (EWRC) have been the recipients of the USFSA’s Food Sovereignty Prize, which recognizes “international and national organizations making significant strides towards food sovereignty.” Additionally, Agrarian Trust is part of the Nyeleni Process, a collaborative effort of grassroots organizations around the world working to [articulate] the next phase of the food sovereignty movement. Through these efforts, Agrarian Trust and its partner organizations are an active force in the global struggle for food sovereignty and the creation of a more democratic, equitable and ecologically grounded relationship with the land.

What Is Food Sovereignty?

The concept of food sovereignty was first articulated at the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome, Italy by Via Campesina, an international coalition of “over 200 million small-scale farmers, peasants, farmworkers, and other food producers in over 70 countries.” In opposition to proponents of the Green Revolution, who argued for the technification of agriculture and the use of industrial farming techniques to increase food production, advocates of food sovereignty championed local control of the land, Indigenous knowledge, and farming practice, and self-sufficiency as essential components of the global food system. The concept was further explored in 2007, at the first Nyeleni Conference in Selingue, Mali. In the Declaration of Nyeleni, representatives of grassroots organizations and small-scale farmers around the world defined food sovereignty as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” This, argued the Nyeleni delegates, means placing the needs and aspirations of local communities, rather than the greed and ambition of corporations, at the center of food production.

In 2013, the US Food Sovereignty Alliance became the steward of the Food Sovereignty Prize, an award that recognizes organizations internationally and domestically who have made significant contributions to the food sovereignty movement. As opposed to the World Food Prize, which celebrates technical advancements that accumulate wealth and knowledge in the hands of only a few international agribusinesses, the Food Sovereignty Prize celebrates a diversity of approaches to stewardship of the land, including the revitalization of local communities, and the growth and preservation of Indigenous knowledge. As a USFSA spokesperson in 2020 awards ceremony] put it, “the World Food Prize promotes the myth that hunger is due to a lack of production, when we know that in fact it is due to a lack of justice.”

Agrarian Trust initiatives such as FaithLands and the Agrarian Commons embrace the redemptive potential of community-controlled land, social justice, and ecological farming practices—principles that are closely aligned with the objectives of the USFSA. As such, it is no great surprise that Agrarian Trust and its partner organizations stand out as leaders in the US food sovereignty movement.

Food Sovereignty and the Agrarian Commons

In 2020, the Somali Bantu Community Association (SBCA), a Maine-based organization dedicated to providing transitional services, advocacy, and food security to members of the Maine refugee community, was the domestic recipient of the Food Advocacy Prize. The SBCA worked with Agrarian Trust to purchase a 104-acre farm in Wales, Maine and place it under the stewardship of the newly created Little Juba Agrarian Commons. Now “200+ Somali Bantu farmers can grow their own, culturally preferred foods … have enhanced food security via better control of the source of their food” on the newly created Liberation Farm. Where in the past, the SBCA struggled with the drawbacks of short-term leases, such as the challenges of investing in long-term soil health and infrastructure, the Agrarian Common’s 99-year lease ensures that the Somali Bantu community will have access to arable land for decades to come.

The Little Juba Central Maine Agrarian Commons, along with other community programs run by the SBCA, has become an important gathering point for the Somali Bantu community. According to SBCA founder Muhidin Liba, “when we started the farming program, for the first time, people are meeting outside their houses. People are breathing fresh air, people are sweating on the farm, people are producing food.” The tireless organizing of grassroots groups like the SBCA serve as living proof of the principles of the global food sovereignty movement. Land is not just a resource to be drawn upon to increase food production, it also serves as the foundation of resilient local food systems, vibrant local cultures, and thriving communities.

A similar ethos informs the work of the 2021 recipient of the Food Sovereignty prize—the Eastern Woodlands Rematriation Collective (EWRC). Led by urban Indigenous women and two-spirit individuals in Massachusetts, the EWRC works to “sustain the spiritual foundation of our livelihoods through Indigenous food and agroecological systems.” Toward this end, EWRC places the knowledge and power of Indigenous women and two-spirit individuals at the center of their work. “In a matriarchal framework, power becomes transformative,” writes EWRC, “Rematriation re-powers our people and allows us to remember that we have what it takes to live healthy, balanced lives. By centering Indigenous womxn and Two-Spirits as medicine people, midwives, and food producers, we are rematriating our food and economic systems in a way that’s more resilient and just.” EWRC leads a range of programming dedicated to valorizing Indigenous knowledge as a means of ensuring Indigenous self-sovereignty and security. These include an apprenticeship program in Wabenaki herbalism, educational seminars on food and land access rooted in the values of rematriation, and a mutual aid network for supporting community members impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Most recently, EWRC has been working with Agrarian Trust to return land to Indigenous control in the form of the Black Swamp Agrarian Commons.

Grassroots organizations like the SBCA and the EWRC are the engines of the growing international food sovereignty movement. At the same time, Agrarian Trust recognizes the importance of placing local struggles within a global context, and of coordinating with organizations around the world to halt the destructive rampage of global capital. For this reason, Agrarian Trust is an active participant in the Nyeleni Process, an effort of like-minded organizations around the world to envision together the next chapter of food sovereignty. Participating organizations will identify opportunities for growth and change within the food sovereignty movement, before setting the priorities for the next Nyeleni Conference, which is expected to take place in March 2023.

In a world quickly being destroyed by the profit motives of global finance, it is easy to accept a degraded environment, the loss of communities, and the centralized control of land as inevitable consequences of modernization. The actions of the EWRC, the SBCA, the US Food Sovereignty Alliance, and countless affiliated organizations show us that this is anything but the case. Not only is an alternative to the current system of land tenure on the horizon, it already exists in the actions of Indigenous organizers, refugee communities, small-scale farmers, and grassroots organizations around the world, struggling for a more just, equitable, and intimate relationship with the land.

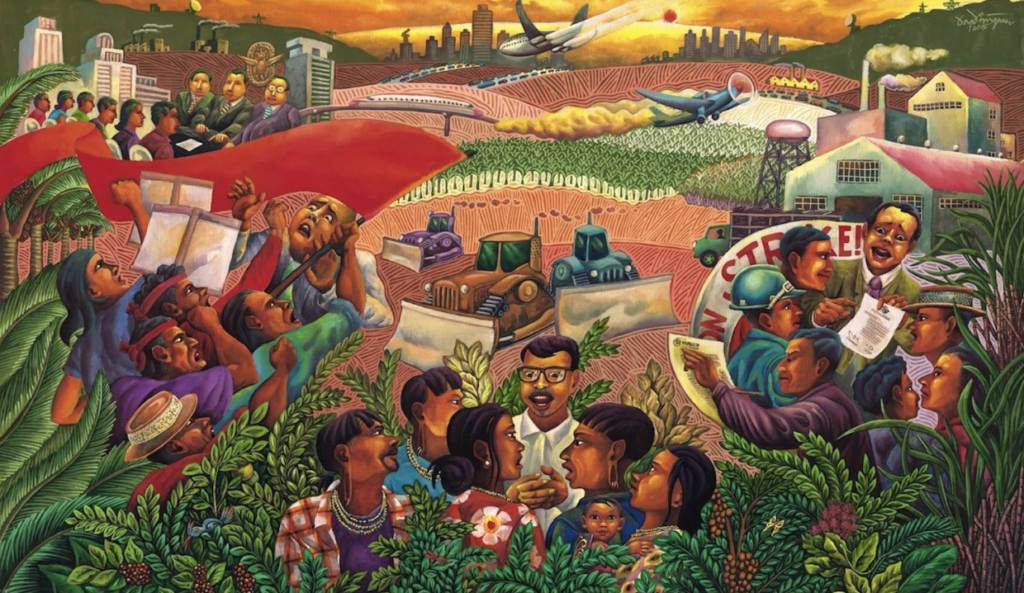

Header photo credit: Painting by Boy Dominiguez for Journal of Peasant Studies special issue ‘Political Reactions from Below’